|

Besides receiving and visiting Our Lord in the Blessed Sacrament at Mass and Adoration, I find that the most nourishing aspect of my spiritual life is friendship with the saints. The Church holds celebrating the saints and asking for their intercession in high regard, as the Solemnity of All Saints, which falls on November 1st each year, is a holy day of obligation. The Vigil of All Saints, then, falls on October 31st each year. One goal of the Christian is to engage in prayer with God, and prayer, simply put, is conversing with God. Each day, we can offer our work to God and talk to Him frequently. This is not always easy, though, and I have found that friendship with the saints helps immensely. A friendship, which is the mutual willing of the good between people, is cultivated with communication and time spent together. Aristotle and Shakespeare, in their genius commentaries on friendship, always return to the simplicity of authentic friendship. Developing a friendship with the saints does not need to be overly-complex. It can also be founded upon communication and time spent together, ultimately bringing us closer to God and strengthening our communication with Him. Communicating daily with the saints further orients our minds to the supernatural, to the existence of the “things…invisible” that we recite in the Creed, and it also strengthens us in the fight for our souls. By communicating with the saints, we will become more like the saints, who in their devotion to Christ became like Christ. Thus, the saints will help us to become more Christ-like. The poet Gerard Manley Hopkins gets at this point in one of his poems: I say móre: the just man justices; Keeps grace: thát keeps all his goings graces; Acts in God's eye what in God's eye he is -- Chríst — for Christ plays in ten thousand places, Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his To the Father through the features of men's faces. The “just man” is the saint, and the saint’s Christ-like actions help him to become like Christ. As I mentioned in my last blog, stories of the saints are dramas of the highest caliber. Each saint had a unique personality and found their way to heaven in their own special, grace-filled way. There are so many saints that everyone can find someone they relate to or want to emulate. Below, I have listed just a few of my friends, and I pray that they will intercede for you! Sts. Peter and Paul, St. Edmund Campion, St. Ignatius, St. John the Beloved Disciple, St. Luke, St. Catherine of Sienna, St. John Paul II, Bl. Pier Giorgio Frassati, Bl. John Henry Newman, Sts. Thomas More and John Fisher, St. Robert Southwell, St. Henry Walpole, St. Aloysius Gonzaga, St. Robert Bellarmine, St. John Berchmans, St. Francis Xavier, St. Leo the Great, St. Augustine, St. Vincent Pallotti, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Therese of Lisieux, St. Teresa of Avila, St. Josemaria Escriva, St. John Vianney, St. Joseph, Guardian Angels, Our Lady… Ora pro nobis!

0 Comments

Being comfortable with dependence is a struggle for me. I absolutely hate to be a burden on anyone. In fact, my family constantly reminds me that it’s OK to ask for assistance and guidance. Several years ago in college, for example, I began to have car troubles that created a need for help with transportation. My parents reminded me that my friends would be there for me to lean on, reassuring me that they would in fact be glad to help. I was pleasantly surprised when each friend I asked for help gave a resounding, “Of course!” Self-reliance seems to be a virtue valued by society because we are taught that it is better to give to others than to take. But when taken too far, the negatives of this quality actually erode our trust and relationships with other people, as well as our desire for God. In the Acts of the Apostles, we learn how the members of the early church relied upon one another and became stronger because of this support. We are humbled when we rely on others and on God, but we are also brought closer together as a result. Recently, I read about Jabez’s prayer in the Bible. Jabez calls out to God asking, “Oh, that you may truly bless me and extend my boundaries! May your hand be with me and make me free of misfortune, without pain!” Jabez turns to God in prayer, showing strength in dependence on God. Dependence is synonymous with prayer. It requires humility, an acknowledgement that we need God to help us grow and become more like him. 1 Peter 5:7 says, “Cast all your worries upon him because he cares for you.” God wants us to ask for his blessings in prayer, to strive for big goals and dreams, not settle for mediocrity. But in all we do, we are called to glorify the Father, just as Christ did on earth. Although not every one of our prayers is answered in the way we ask, God does hear each one and answers them in some way. Sometimes, an answer may come in the form of hardship or suffering. Conversely, an answer may come in the form of silence. Other times, an answer may come as blessings, an “extension of boundaries.” Regardless of the outcome of our prayer, God invites us to depend on him in the midst of any situation we may find ourselves in – whether we are in a position of strength or weakness. With time, experience, and prayer, God continues to show me how to reach out to others as resources and guides. Over the summer, I began to pray something like Jabez’s prayer. I had asked God for ways to help me become more connected to my parish, and he responded by having a pastoral associate invite me to help form a young adult ministry in the parish. I reached out to other young adult ministry leaders who offered their suggestions and advice, and they put me in contact with other diocesan leaders who were wonderful resources as well. Several friends also offered their support for the ministry and have helped to form a core planning team. Since the ministry had its first event in September, I encounter someone new looking to join or share the ministry with someone else several times a week. We’ve even had other parish ministries ask how the young adults can help be part of their evangelization missions. Our territory is enlarging, as Jabez would say. God, and other people, want to help us and be a part of our lives – we just have to ask. Questions for Reflection: Can you think of a time when you had to rely on the generosity or goodwill of others? How did it make you feel? I recently had the opportunity to attend a marvelous performance of the Sistine Chapel Choir in the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. This was the first visit of the choir, one of the oldest in the world, to the United States in over thirty years, and was sponsored in part by the National Shrine, The Catholic University of America, and the latter’s new Catholic Arts Council. After I arrived, I noticed that it was not long before the nave of the Basilica was filled to capacity. The time before the performance afforded me the opportunity for private prayer and reflection. As I looked around the church, I was awed by the works of art surrounding me and, despite the growing crowd, could sense the spiritual beauty and ambient serenity characteristic of God’s House.

The concert itself was no less awe-inspiring. While the choir’s reputation and skill preceded it, from the very first note, I found myself enraptured by a beauty like no other. The sacred notes were uplifting yet never overpowering, as if they were directing our focus away to something greater. Listening to the notes being individually pronounced captivated the congregation and invited the audience to be placed in a calming yet spiritually-driven mindset. Each work called our attention to God, His works, and His eternal presence. The Catholic Church recognizes music’s beautiful and historic role in the liturgy as an invitation to participate in the mystery of God Himself. As Pope Francis said in his Address to Participants in the International Conference on Sacred Music, “Sacred music and liturgical chant have the task of giving us a sense of the glory of God, of his beauty, of his holiness which wraps us in a ‘luminous cloud.’” Think about the psalms prayed at Mass each day. They are ancient prayers the Church has preserved in Her liturgies! In the psalms, the people of God are able to express the full range of their emotions to Him, such as their joys (like Psalms 98 and 100), sorrows (like Psalms 69 and 88), exhaustion (like Psalm 6), uncertainty (like Psalm 23), and even abandonment (like Psalm 22). The psalms are not simply performances; they convey, guide, and evoke an emotional response from the people of God back to Him Who is the focus of the entire liturgy. By extension, the other hymns we sing at Mass should move us to participate more fully in the liturgy rather than passively watch the processions and preparation of the altar—the Mass is not meant to be watched like a secular performance! Pope Francis expands upon this, saying, [Sacred Music] is therefore firstly a matter of intense participation in the Mystery of God, in the “theophany” that occurs in each Eucharistic celebration, in which the Lord manifests himself in the midst of his people... Active and conscious participation consists, therefore, in knowing how to enter profoundly into this mystery, in knowing how to contemplate, adore and welcome it, in grasping its sense, thanks in particular to religious silence and to the ‘musicality of the language with which the Lord speaks to us.’ Hymns have also been recognized by the Church as an effective means of catechizing the faithful, including the youth. Pope Francis continued, “The various key figures in this sphere, musicians, composers, conductors and choristers of the scholae cantorum, with liturgical coordinators, can make a precious contribution to the renewal, especially in qualitative terms, of sacred music and of liturgical chant.” The works that are crafted by their hands can indeed be a beautiful means of engaging those whose ears the notes fall upon. But in order to be truly esteemed as noble and sacred, they must be holy. “In order to foster this development,” Pope Francis said, “an appropriate musical formation must be promoted, even of those who are preparing to become priests, in a dialogue with the musical trends of our time, with the inclusion of different cultural areas and with an ecumenical approach.” The next time you hear music at Mass, I suggest uniting your voice with the cantor as a prayer to God. The act of doing so invites us to offer to God a part of ourselves that we may regularly try to keep private. Done reverently, it becomes an offering of love to our Lord, as Pope Benedict XVI observed: The singing of the Church comes ultimately out of love. It is the utter depth of love that produces the singing. “Cantare amantis est”, says St. Augustine, singing is a lover’s thing. In so saying, we come again to the trinitarian interpretation of Church music. The Holy Spirit is love, and it is he who produces the singing. He is the Spirit of Christ, the Spirit who draws us into love for Christ and so leads to the Father. Questions for Reflection: How can music impact your experience of the liturgy or of God? Can you remember a time when music helped deepen your faith? As I write this, the weather is gray and cold. It has been raining for what feels like forever, though more accurately it’s been about a week. I miss the summer. I miss a lot of things, and people, when October rolls around. It seems to be a month made for melancholy. Perhaps it is because two of my grandparents died during separate Octobers in my childhood. This month has always been a time of missing them, remembering the past, and grieving. I was eight the October my paternal grandmother died, and she was the dearest person in the world to me. Grief is a word we use to describe the feeling of missing someone or something after they are lost to us forever. We grieve days that are behind us, relationships that never grew, opportunities that we missed. But most of all, we grieve persons. Death seems to be the end of all that is, the end of all who is. It is unbreakable, unbreachable, unending. As Christians, we do not think in those terms because they have been proven false. Jesus Christ, as well as Mother Church, tells us that death is not the end. It is an act of hope to believe this. Death only appears to be final and absolute and unknowable. Through Christ’s resurrection, God has revealed that death is not our final end. It is often hard for us to trust what happens next because we simply cannot know it with the certitude with which we know this world. The Church speaks of the Four Last Things, with Death being the first or entryway to the other three: Judgment, Heaven, and Hell. But that is another topic. What about those of us who remain on earth while a loved one has gone ahead? What do we do? How do we live with loss? C.S. Lewis told a friend who had recently lost his beloved wife, “Sad you must be at present. You can’t develop a false sense of a duty to cling to sadness if– and when, for nature will not preserve any psychological state forever– sadness begins to vanish” (A Severe Mercy, Sheldon Vanauken). Of course we feel sad as a result of someone’s death. A loved one who brought joy and lightness into our hearts has gone, and our sadness is a natural response. There is no Christian commandment forbidding sadness. It is an emotion, which is neither good nor evil. Emotions just are. They come and go, washing over us. If we choose to take them too deeply within ourselves, however, emotions can become dangerous. We can drown in grief, for example, if we make it our cosmology. And the Christian is commanded to have the same mind as Jesus Christ. He sees the world with the eyes of resurrected love. While we may not always be able to choose our emotions, we can choose our attitude and our response to them. Joy, even in the midst of sadness, “comes of being loved” wrote Pope Benedict XVI in Deus Caritas Est. And love has conquered death in a singular act. Jesus, the Christ, the Second Person of the Trinitarian Godhead, the Son of the Father, died on a cross to redeem us from an unredeemable bondage because he loved us and desired us to be with him. It is to that reality that we must orient ourselves. Grief can too easily turn us inward. Like a black hole, it can devour everything surrounding it so that it is the only thing left. Love perpetually calls us out of ourselves, and asks us to give ourselves as a gift, even and especially in the hard times. I do not doubt that God’s heart broke when humanity sinned the first time, and breaks again at every subsequent sin. But God did not become consumed by grief at our fall. God is love, and love gives of itself to the beloved unceasingly. Therefore, God acted in order to redeem mankind. I want to tell you more about the process of grief, of going through the stages of denial, anger, bargaining, depression and, finally, of reaching acceptance, but I don’t know your process. I don’t know your specific loss, which we all must face at various times of our lives. That’s okay. We can hold a space for each other as we go through the process of grieving. We can let each other remember and smile and laugh and cry and long for the missing one, repeating this process as necessary. As a recent homily reminded me, our God does not tolerate idols in our lives. Our grief cannot consume our love, or else it makes a golden calf of our beloved. May our love of God, united with the love our dearly departed, orient us to the loving heart of the Father. May we know that this present sadness is not the end. Question for Reflection: Have you grieved the loss of something in your own life? How has your faith impacted your experience of grief?

Today we celebrate the sixth anniversary of the Catholic Apostolate Center. In these six years, we have been to countless conferences; developed relationships with numerous national organizations and dioceses; shared thousands of saint images on Facebook; emailed hundreds of newsletters; and collaborated with bishops, priests, religious, diocesan officials, lay ministers, and Catholic leaders from around the world. In these six years, we have appreciated the collaboration with each and every one of you and look forward to continued development of programs and resources to revive faith, rekindle charity, and form apostles.

In celebration of this anniversary, we invite you to view our updated introduction video of the Center. This video highlights the mission of the Center and our constant desire to live as missionary disciples. Please be assured of our prayers for you through the intercession of Mary, Queen of Apostles and St. Vincent Pallotti, patron saints of the Catholic Apostolate Center. May the Charity of Chris urge us on! Changing diapers. Making dinner menus for the week. Vacuuming raisins out of the deepest crevices of the car’s backseat. Often, the daily tasks of running a household and raising a toddler feel more to me like mindless drudgery than fruitful and productive labor. My inner monologue ends up sounding like this: My husband works eight hours a day at a meaningful job that he enjoys, and his income puts a roof over our heads, food on the table, and clothes on our backs. And what do I do? Sweep floors that are just going to instantly get dirty again and scrub toothpaste off the bathroom mirror—which is my own fault because I left the toddler alone while he brushed his teeth this morning.

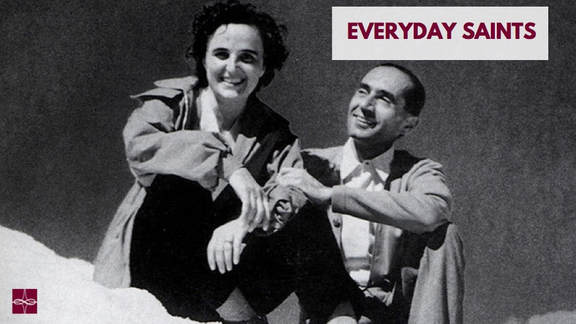

Lately I had found myself searching for examples of saints whose primary vocation was parenthood and family life. And I began to read The Journey of Our Love, a collection of letters written by St. Gianna Beretta Molla and her husband, Pietro. Prior to reading the letters, all I had known about St. Gianna was that one of her pregnancies was extremely difficult and that she ultimately sacrificed her life for her child. I thought this was the only reason that she was canonized in 2004. But as I read the letters St. Gianna and her husband wrote to each other, I gradually realized that Gianna’s self-sacrifice was only the final heroic act of a life filled with profound joy and holiness. On the surface, the Mollas’ married life looks quite typical for the contemporary western world: St. Gianna was a pediatrician who split her time between her clinic and her duties at home, while Pietro traveled frequently for his job as an upper-level administrator for a manufacturing company. Their older children suffered from persistent, but not life-threatening, health issues like severe reflux and hip misalignment. Where the Mollas differ from most modern parents is in their deep devotion to God and in the trust, love, and joy that flowed from placing Christ at the center of their lives. The more I read of St. Gianna and Pietro’s letters, the more I was struck by my own inability to see the greatness that is possible within the most mundane, repetitive, and irritating aspects of domestic life. St. Gianna and her husband did not found any religious orders, nor were they publicly martyred for their faith, nor were they brilliant theologians. Rather, they were ordinary people whose love for Christ permeated every aspect of their lives. One of my favorite examples of St. Gianna’s quiet holiness is when one of Pietro’s overseas business trips, already over a month long, was extended by several weeks. Gianna initially reacted as many wives would do and “had a good cry” (page 209). But then, rather than wallowing in her loneliness or in the difficulties of parenting alone, she writes that she “offered this sacrifice to the Lord for you [Pietro] so that he might protect you during your continual flights, and for the baby we are expecting, so it will be born beautiful and healthy.” Pietro, too, often writes that while he suffers from the long separations from his wife and children, he offers those sufferings so that he and his family will continue to be blessed. Neither St. Gianna nor her husband ever express a sense of doubt about the apparent banality of their lives—they accept their ordinary trials with grace and humility, and are quick to turn their frustrations or sadness back into thankfulness for the good God has granted them in their lives. Reading the Mollas’ letters helped me see that, like St. Gianna and her husband, I am called to be holy in every aspect of my ordinary and seemingly unremarkable life— whether it be caring for a toddler with a persistent cold or doing my fifth load of laundry in two days. For most of us, we are called to be saints not through grand gestures of faith, but in the love with which we embrace the ordinary burdens of our everyday lives. Question for Reflection: What are some ordinary tasks in your everyday life that can help you become an everyday saint? “[Jesus] saw a man named Matthew sitting at the customs post. He said to him, ‘Follow me.’ And he got up and followed him (Matt 9:9).” St. Matthew (a tax collector, dishonest and greedy) accomplishes what usually seems like the most difficult task: simply following Jesus. The calling of St. Matthew reminds us that authentic Christian life is quite simple: Get up and follow Jesus. This could also be summed up in the words of St. Faustina, to whom Jesus revealed His message of Divine Mercy, “Jesus, I trust in You.” As we all know, the Christian life is not always that simple. There is something to be said about why stories of the saints and stories of converts to the Faith are dramas of the highest caliber. I think we can learn a lot about the drama of the Christian life through the works of T.S. Eliot, one of the twentieth century’s major poets. Eliot converted to Christianity in 1927 when he was 39 years of age. He became more fervent in his faith until his death in 1965. Eliot’s poetry is often divided by his conversion. Before his conversion, his notable works are “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” (1915), The Waste Land (1922), and “The Hollow Men” (1925). After his conversion, he is known for “Ash Wednesday” (1930) and Four Quartets (1943). Four Quartets is often considered to be one of the most important works of the twentieth century; it led to Eliot’s winning of the Nobel Prize for Literature, and in my opinion, is the most incredible summation of the Christian life in poetry—only surpassed by Dante’s Divine Comedy (1320). Without revealing too much about the poem (I hope that you will read it here!), I wish to share with you a relevant section. Eliot writes about the saints whom we should emulate, and how difficult that is: And what there is to conquer By strength and submission, has already been discovered Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope To emulate - but there is no competition - There is only the fight to recover what has been lost And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss. For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business. This section can be found in the second of the Four Quartets, “East Coker,” in the final section of the poem, section five. On one level, Eliot is speaking about writing, and the timeless struggle to produce great literature. He is probably referring to Shakespeare, Dante, and other great authors in regards to emulation. On another level, Eliot is commenting on the Christian life and emulating the saints that have come before us. Eliot speaks of the struggle of living an authentic Christian life— “There is only the fight to recover what has been lost / And found and lost again and again.” But he sums up the task of Christian life quite simply, like the Scripture passage in the calling of St. Matthew: “For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.” We shouldn’t let ourselves be consumed with all the exterior drama and complications of everyday life (though these things are important to function effectively in the world), but with the simplicity of Christian life. Get up and follow Jesus, and don’t ever stop trying. And read some TS Eliot in your spare time! Question for Reflection: What prevents you from simply getting up and following Jesus? “Practice patience toward everyone and especially toward yourself. Never be disturbed because of your imperfections but always get up bravely after a fall.” -St. Francis de Sales A few years ago, I had the opportunity to travel to Rome, Italy. To this day, the pilgrimage showers graces into my life. One day on the pilgrimage, we went to the Basilica of Sant’Agostino and prayed in front of a painting by Caravaggio called the Madonna di Loreto. In it, Caravaggio paints dirty, unkempt pilgrims kneeling in front of Our Lady and Jesus. Two years later, the image is still embedded in my mind. The Rome pilgrimage seemed to be a small microcosm of my life. My struggles and weaknesses were the same struggles and weaknesses I encountered back at home and work, yet in Rome they had a different weight. My frustrations with my weaknesses were still there, but it wasn’t until I was looking up at that painting that I realized that the pilgrimage was a process. My sin and weakness, my toil, my striving for sanctity—all of this was a process. The walking, the waiting, the impatience, the stumbling, the praying, the joy, the suffering—all was part of my pilgrimage and contributed to the end or goal: sanctity. I found myself praying for patience, and was informed by a fellow pilgrim that the root word of patience is “to suffer.” I found this definition fitting for the journey. Today, we are all on a pilgrimage aimed toward Heaven. In my walk, I find myself quickly frustrated at my stumbles, my repeated sin (that for some reason I just cannot get over), my judgment, my lack of love, and the list could go on. This frustration with the pace of my walk on the pilgrimage to salvation is not helpful for the walk—it is inhibiting. My walk requires patience with others and with myself. Looking at that painting by Caravaggio, I realized that we are the pilgrims—dirty from the journey, imperfect, on our knees asking Our Lady for the gift of her Son. He receives all of us as we are on this walk, and patience in the process will lend to an easier recovery after a stumble, a lighter load to carry. Let us grant ourselves patience throughout our pilgrimage to our end, Jesus Christ. As St. Teresa of Calcutta reminds us, “We have only today. Let us begin.” When was the last time you thought about St. Joseph? For many, he is a shadowy figure. And yet, he is recognized as the "protector" of the Church. His feast day is March 19th. What's your image of Joseph? Is he young or old? Is he working or sleeping? Is he rich or poor? Is he strong or weak? We invite you to clear away all those images in order to see him for the first time. Let's meet Joseph as he is presented to us in the Gospel of Matthew at the birth of Jesus. Of course, the best thing to do is to pray with Matthew 1:18-25. Here’s the abbreviated version: Mary and Joseph are engaged. She is expecting. He intends to divorce her quietly but learns, in a dream, that she is carrying a son who will "save his people from their sins" (Matthew 1:21). Joseph is told to accept Mary as his wife and name the child Jesus. In this passage, we see four qualities in Joseph—compassion, righteousness, fidelity, and decisiveness—that make him a saintly man and a role model for us today. Imagine how Joseph felt about Mary's pregnancy. The marriage customs of his day were much different than ours. Were they "in love" or was the engagement arranged? Perhaps Joseph felt more hurt than angry—or perhaps disappointed, given Mary's natural innocence. In any case, he responded with compassion; He did, however, want to do what is right. While he never says a word in the Gospel narrative, Joseph's actions continually say "yes" to God's will. He takes Mary into his home as his wife. He honors Mary's special relationship with God by not having "relations with her until she bore a son" (Matthew 1:25). He claims Jesus as his son by naming him. Joseph lived a quiet fidelity expressed in action rather than words. A kind-hearted man who accepted the mystery of salvation entrusted to him, Joseph adopted Jesus and raised him as his own. He protected him, taught him, and loved him. In the Gospels, Jesus is known as "the carpenter's son." Joseph's love for Mary and Jesus sharpened his awareness of the forces around them. When Herod threatened the life of Jesus, Joseph leapt into action, leaving that night for Egypt. When the threat was gone, he brings Jesus back to his people. When he realized some threat remained, he settled in Nazareth, thus fulfilling a prophecy. His actions were always for the good of Jesus and Mary, and ultimately a part of God's plan for salvation. As we get closer to Joseph, we meet a kind-hearted man, walking humbly with his God, as he accepts, protects, and raises Jesus so that Jesus can "save his people from their sins." St. Joseph can shed considerable light on what it means to be a missionary disciple in an increasingly secular age—with implications for the economy, family, and mission. He plays a quiet, but essential, role in salvation history. Perhaps we, too, have a quiet role to play in salvation history. Perhaps Jesus is relying on us just as he relied on Joseph. Compassion, righteousness, fidelity, and decisiveness can help us live out our role just as they served Joseph. What does the word adoption mean to you? Joseph's vocation began with a dream—a message from God. He is commanded to "rise, take the child" as his own. When we engage the world, do we possess it or does the world possess us? Do we adopt friends, jobs, things—even children, seeing them through the eyes of God? Adoption is a way of being in the world. We are adopted children of the Father in Christ Jesus. We are claimed by God and so we, too, can claim others and make them our own - being possessed in the best sense of the word. Joseph adopted—Jesus, Mary, and his life as a carpenter in fidelity to God who, with and through Jesus, was saving the world. St. Joseph, pray for us.

|

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

About |

Media |

© COPYRIGHT 2024 | ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

RSS Feed

RSS Feed