|

Perhaps not surprisingly, I have found myself thinking about sickness lately. From colds, to Covid, to cancer, it’s likely you know someone who is sick, are caring for a sick family member, or are sick yourself.

Being sick is miserable and caring for someone who is sick is no picnic either. It is hard to watch our loved ones suffer. The Catechism counts illness and suffering among the “gravest problems confronted in human life. In illness, man experiences his powerlessness, his limitations, and his finitude” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1500). The way we respond to sickness can tell us a lot about ourselves. The Catechism describes two different responses: “Illness can lead to anguish, self-absorption, sometimes even despair and revolt against God. It can also make a person more mature, helping him discern in his life what is not essential so that he can turn toward that which is. Very often illness provokes a search for God and a return to him” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1501). While possible reactions are not limited to these two, I tend to fall into the first category. I often respond to illness by wallowing in self-pity and self-indulgence. When I contemplate saints who suffered terrible illness without complaint, I feel as though I fall very short. Can I really live my sickness or that of my loved ones in the presence of God? If I remain wrapped up in myself, sickness is simply misery. But if I am open to receiving the grace of God, it’s a very different story. Take today’s readings for instance. On today’s feast of the Conversion of St. Paul, we hear about his reaction to being struck down and left blind, weak, and clueless. How does Saul (later known as St. Paul) respond to his illness? He allows himself to be led by the hand and, under Ananias’ care, recovers his sight and regains his strength. Ananias’ role in this healing is remarkable. He responds to God’s call to care for Saul, who just before had been “breathing murderous threats against the disciples of the Lord” (Acts 9:1). Ananias goes so far as to call Saul “my brother” (Acts 9:17) and nurses him back to health, despite having many reasons that might justify doing otherwise. Ananias exemplified Christ’s own compassion toward the sick and his ministry of healing. “Moved by so much suffering Christ not only allows himself to be touched by the sick, but he makes their miseries his own: ‘He took our infirmities and bore our diseases’ (Mt 8:17; cf: Isa 53:4)… By his passion and death on the cross Christ has given a new meaning to suffering: it can henceforth configure us to him and unite us with his redemptive Passion” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1505). Though we may sometimes feel abandoned in our illness, Christ is not indifferent to our suffering. On the contrary, he has made it his own, and, through his own suffering and death, Christ has transfigured it. When we respond to illness with a desire “to freely unite [our]selves to the Passion and death of Christ” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1499), suffering takes on a new meaning. It can be an opportunity to become more like Christ and to participate in the saving work of Jesus. This in no way downplays or dismisses the difficulties and challenges of being sick, but rather elevates them and transforms them into something greater, something which contributes “to the good of the People of God” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1499). Let us allow today’s readings to prompt us to examine our own attitudes towards sickness and suffering, especially if we find ourselves in the position of caring or being cared for. How can we, like St. Paul, allow ourselves to be taken by the hand? How can we more readily and gratefully accept help in our illness? How can illness serve to draw us closer to God and make us more Christ-like? How can sickness make us more mature and help us to recognize what is essential? How can we be more open to the grace of God which can offer us the strength, peace, and courage to overcome the difficulties that come with sickness? How can we, like Ananias, respond to God’s call to bring his healing to others? How can we lovingly lead our sick loved ones out of anguish, self-absorption, or despair? How can we imitate Christ in our compassionate care for the sick and suffering? To visit our COVID-19 Resource Page, please click here.

0 Comments

Tomorrow, we celebrate the birthday of St. Vincent Pallotti, patron of the Catholic Apostolate Center and founder of the Union of Catholic Apostolate. St. Vincent Pallotti was born on April 21, 1795. How appropriate for the saint who lived and worked in the city of Rome to share his birthday with the traditional date for the founding of the city. To help celebrate his birthday, I have put together a list of some of his more interesting achievements and activities during his life. I hope that you too will be inspired by his life. 1) The Baptism of St. Vincent Pallotti St. Vincent Pallotti was baptized on April 22, 1795 in the St. Lawrence Church in Rome. This began his life in the church. 2) St. Vincent Pallotti on Holiday On his arrival in Frascati around 1805, St. Vincent Pallotti exchanged his new shoes for that of a poor boy. Giving away his new clothing to the poor would become a lifelong habit for the saint. 3) St. Vincent Pallotti Makes a Prediction While speaking with the young Giovanni Mastai-Ferretti in 1817, St. Vincent Pallotti predicted that he would one day be elected to the papacy. Mastai-Ferretti was elected Bishop of Rome on June 16, 1846. 4) St. Vincent Pallotti the Professor St. Vincent Pallotti was awarded two doctoral degrees in both theology and philosophy in 1814 and 1819. Teaching was one of the favorite activities of the saint. 5) St. Vincent Pallotti Showing Courage During the cholera epidemic of 1837, St. Vincent Pallotti organized a barefoot procession of religious. This action was penitential and showed that they were not afraid of the disease. 6) Catholic Apostolate Received Church Approval St. Vincent Pallotti received approval for the Catholic Apostolate from the Church in 1835. Pallotti also received support for the Catholic Apostolate from Pope Gregory XVI when others objected to it. 7) St. Vincent Pallotti the Chaplain Beginning in 1838, St. Vincent Pallotti served as a prison chaplain in Rome. He often worked with the condemned, saving many souls. He had a true willingness to serve all, especially the poor and the marginalized. 8) St. Vincent Pallotti the Peacekeeper St. Vincent Pallotti stopped a riot in the Trastevere neighborhood of Rome. He implored the people to stop rioting by showing them an image of Mary, Mother of Divine Love. 9) St. Vincent Pallotti Preaches one Last Time On the last day of the octave of the Epiphany in 1850, St. Vincent Pallotti gave his final sermon. 10) St. Vincent Pallotti Dies In 1850, St. Vincent Pallotti gave his final blessing to his followers. He showed great courage even in the face of death. There are many more stories about St. Vincent Pallotti that you may find interesting. Check out our St. Vincent Pallotti Portal to learn more about our patron and his many works. I would like to begin this monthly recollection talk by stating the reason why I was chosen as the preacher. Owing to the current situation of the Coronavirus pandemic, the preacher chosen for this monthly retreat, Fr. Louis Caruna SJ, Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy at the Pontifical Gregorian University (Rome), was unable to come. Incidentally, two weeks ago, I had written - in Polish - an article on Pallotti's commitment during the cholera epidemic in Rome in 1837. The rector of our community had obviously seen it, and had probably read it, so he asked me to develop it a bit more and then deliver it for the recollection. Thus, I now stand as the ‘extra cog’ – a cog as significant as the real cog for any machine, even for the machine called ‘the community.’ The following four texts served as the main sources for my reflection. They are: Francesco Todisco, San Vincenzo Pallotti: Profeta della Spiritualità di Comunione; Francesco Amoroso, San Vincenzo Pallotti: Romano; the ancient but the excellent Dizionario di Erudizione Storico-Ecclesiastica by Gaetano Moroni; and the letters of Pallotti. The 1830’s, especially the years between 1835 and 1837, were years of great suffering for Europe because of the cholera epidemic, which was then known as the ‘Asian epidemic’ because it had originally come from India (part of today’s Iraq). In previous centuries, epidemics spread from city to city starting from port cities such as Civitavecchia, Genoa and Naples. The cholera epidemic began differently when it reached some Baltic countries, such as Poland, as early as 1831. Then in 1832 the epidemic reached England; in 1833 it was brought to Ireland, Portugal and the Netherlands. It then spread to France in 1835. As the epidemic was spreading, it left behind a long trail of death (Moroni, 233-243). The spread of the disease was quick. In Italy, the first epidemic deaths occurred on September 13th, 1835. As a preventive measure to preserve the Eternal City from the disease, Pope Gregory XVI ordered, without any delay, the exposition of the most distinguished Christian relics for the common veneration in the churches where they were present. Here I want to specify the relics considered to be important for common veneration both in times of solemn and difficult occasions in 19th century Rome. These details are taken from Moroni’s book (Dizionario di Erudizione Storico-Ecclesiastica). They were: · The skulls of the apostles Peter and Paul in the Lateran Basilica; · The holy face of Veronica and the finger of St. Peter in the Vatican Basilica; · The body of St. Pius V in the Basilica of Saint Mary Major; · The Wood of the Cross and the Thorn of the Crown in the Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem; · The scourging pillar in the minor Basilica of St. Praxedes (Basilica di San Prassede); · Two celebrated crucifixes – one in St. Lawrence in Damaso (a minor basilica) and the other in the church of St. Marcello al Corso; · The imprisonment chains of Sts. Peter and Paul in the Basilica of St. Peter in Chains; · The arm of St. Roch, the protector against the plague in the church of St. Roch in Lungotevere, Ripetta; · The arm of St. Francis Xavier in the church of Gesù (the mother church of the Society of Jesus); · The bones of St. Sebastian in the minor basilica of St. Andrew of the Valley (San Andrea della Valle). Pope Gregory XVI also ordered the celebration of an extraordinary novena to be held from August 6th-15th, 1835 in all the fifteen churches dedicated to Mary [in Rome] in preparation for the feast of the Assumption of Mary, By July 31st, 1835 the Cardinal Vicar Odescalchi had published a decree L’invito Sacro (The Holy Call), which was fixed on the doors of all the churches. However, this document does not have much in common with the decrees issued by Cardinal Angelo De Donatis (also posted on church doors) on March 8th, 12th, and 13th, 2020. The decree signed by Cardinal Odescalchi reveals the 19th century mentality regarding the epidemic. I will cite a few lines: A fatal disease, which for the obscurity of its origin, for the extravagance of its progress, for the uncertainty of its attacks, appears for the believers, to have the features and signs of a scourge. Will Rome be immune from it (dispensed from it)? Oh! Romans, do not delude yourselves! Yes, Rome has failed its duty. The Holy Name of God is trampled on; feasts and solemnities are desecrated, and with what an insolence the vice roams the streets of the Holy City! So if Rome has failed its duty, it must again be scourged. Oh! Unhappy Rome, only with MARY covering the city with her mantle, the arm of the Angel of End Times that is waiting to empty the poisonous cup on the poor guilty children, can be held back. So, let us all turn to MARY. Cardinal Vicar Odescalchi had some concrete proposals. On the positive side, there was the announcement of an extraordinary novena for the occasion of the feast of the Assumption of Mary in all the fifteen churches dedicated to her. On the negative side, many public gatherings were also forbidden. Specifically, during the period of the novena, taverns, places selling alcohol and most other places of entertainment were all closed. The one exemption was coffee shops. The great Roman poet Giuseppe Gioachhino Belli composed numerous sonnets expecting to exorcise the city of the impending arrival of the virus. Some of the letters of Pallotti from this period of time reveal that he was committed to promoting the initiatives announced by Cardinal Odescalchi. Another preventive and interesting initiative started by Pope Gregory XVI was the procession with the icon of the Madonna Salus Populi Romani - that is "Salvation of the Roman People" (some translate as "Protector of the Roman People"). In fact, the pope had ordered that on September 8th, 1835 the icon of the Madonna Salus Populi Romani should be carried in procession from the Basilica of St. Mary Major (Santa Maria Maggiore) to the Vatican Basilica (San Pietro). This is the famous icon, the icon par excellence of Rome (The icon of the Eternal City), that Pope Francis kneels in front of as he starts and ends each of his apostolic journeys. The icon Salus Populi Romani has a very close connection to the history of the Eternal City and the Supreme Pontiffs. It is believed to have been painted by the St. Luke the Evangelist and it was seen as the reason for victory against epidemics and plagues as well as the reason for many other miracles. Il Diario di Roma, a periodical of the time, explained that the pope had ordered the procession to “assure the souls of the powerful protection of the great Mother of God who regards with delightful eyes this Seat of Christianity [Rome].” Unfortunately, the procession in which the pope walked barefoot was accompanied by such bad weather that this icon of the Virgin Mary was forced to stay for eight days in the New Church (Chiesa Nuova also known as Santa Maria in Vallicella). The return journey of the icon from St. Peter’s Basilica to the Basilica of St. Mary Major was also disrupted by bad weather. In its return journey, the icon Salus Populi Romani had to stay for a long period of time in the Church of Gesù. It finally reached the Basilica of St. Mary Major on September 30th, 1835. The Spread of the Epidemic: The Report of the Physicians, Newspapers and the Church: In Rome, the medical practitioners exhorted people not to be afraid and not to worry. They also forbade the public from talking about deaths and burials, believing as if optimism and joy fortified people against the attacks of cholera. In addition, the medical practitioners urged people to keep their homes very clean. The General of the Society of Jesus, Fr. Jan Roothaan (whom Pallotti knew very well), had personally vowed to celebrate the feast of The Immaculate Heart of Mary every year if the Jesuits in Rome who had given themselves generously for the care of the sick and were in the frontline fighting the contagion, were spared from the disease. Despite all these attempts, by July 1837 the fear of the epidemic had penetrated all social levels. On July 5th Fr. Vincent Pallotti began a Triduum of prayers with a particular intention seeking favors for the people of Naples, the port city where the epidemic had already penetrated. In the Triduum, Pallotti also blessed the food eaten by infected people so that they may be protected by God. On July 29th, Il Diario di Roma launched an attack on its front page on people who were spreading news about the cholera epidemic. It declared itself the right authority on the news pertaining to the spread of the epidemic and said: “[We] deny completely the ill-founded rumor already spread in Rome, that some individuals in the Capital had contracted the Asian cholera.” But the people knew better. They gave little credit to the journals. They knew very well that the newspapers and journals only intended to avoid panic in the city. On August 6th, 1837, the icon of the Virgin (Salus Populi Romani) was again brought in procession to the Church of Gesù. This event was recorded by Il Diario di Roma. According to the report, a squad of soldiers on horseback went before the procession and the procession itself was led by the pupils of the Apostolic Homes and Orphanages. Following them were members of the clergy with candles or torches. The clergy also took turns reciting the rosary. Next in the procession was the icon surrounded by some Jesuits. Everyone else was shut off by the Swiss Guards. The procession went around Via Quattro Fontane and Via del Quirinale. Pope Gregory XVI, the College of Cardinals and the senator of Rome (Prince Orsini – Duke Domenico) joined in the procession as it reached Via del Quirinale. Together, the procession moved slowly towards the Church of Gesù where the Madonna was received by the General and members of the General Curia of the Society of Jesus. The litanies were then sung, and the pope concluded the procession with the final blessing. On August 15th, a grand procession was organized from the Church of Gesù to bring the image of the Madonna Salus Populi Romani back to the Basilica of St. Mary Major (Santa Maria Maggiore). Acting on the exhortation of the Cardinal Vicar, Fr. Vincent Pallotti workedt to organize a sizable group of clergymen who would walk barefoot with him in the procession. The group started its journey from the Church of the Holy Spirit of the Neapolitans located in Via Giulia. To organize this group of religious and diocesan clergy, Pallotti made the best use of all his acquaintances. Pallotti wrote to Fr. Efisio Marghinotti, one of his friends and collaborators: “I ask you humbly, if possible, to inform many clergy of tomorrow’s barefoot procession. Also inform the Abbot Bianchini that even if he could not walk barefoot he could at least direct [the procession]. Tell everyone to get at least twelve others or more [for the procession]. We meet in the Church of the Holy Spirit.” (OCL II, p. 199) In spite of the efforts, the situation in Rome was not good. It is said that fear is the mother of all excesses. This was proved right. On the evening of August 14th, an English Language teacher was killed by a crowd of people near Piazza del Campid’oglio because the victim was believed to be an "anointer" who spread the disease by anointing people and things. The optimism advised by the medical experts was not of much use. Neither could the prayers contain the natural course of the epidemic! Finally, on August 19th, 1837 Il Diario di Roma admitted what was already evident. It said that according to the opinions of the medical doctors, the Asian Cholera had entered Rome. By the beginning of September, the Count Antonio Maria Plebani, who was residing in the region of Marche but whose son was studying in Rome, had already sent a letter filled with grievances to Pallotti. In the letter, he affirmed that there were reasons to worry this time: “cholera, earthquakes, wars, hunger …” Fr. Vincent Pallotti replied saying: “Let us seek God. Let us seek Him always and in all things. And we will find Him and in Him we will all be saved.” (OCL II, p. 206) Meanwhile, in the same period of time, Giovanni Marchetti, a married lay person and a collaborator of Pallotti from Gubbio, wrote to Pallotti asking how he could escape the epidemic. Pallotti replied advising him not to escape from God, but to look for a way to not merit punishment of God. Pallotti wrote: “Hold firm to the maxim that there is no escaping from the Divine scourge. In order to not deserve it, it is better to attend to one’s proper duties.” (OCL II, p. 208) Pallotti’s Response to Cholera: Let us now look at the response of Pallotti to the cholera epidemic. Inside the Church of the Holy Spirit of the Neapolitansthere is a plaque with an inscription bearing the works undertaken by Pallotti as the rector of the church. The inscription reads: “From 1835 to 1846, St. Vincent Pallotti, the Roman priest, was the rector of this Church of the Holy Spirit of the Neapolitans: · He founded the Union of the Catholic Apostolate. · He founded a College for the Foreign Missions. · He celebrated the First Epiphany Octave. · He celebrated the Marian Month of May for the clergy and the faithful. · He animated the spiritual conference of the clergy. · During the cholera epidemic of 1837, the people of Rome recognized in him a holy priest and in his work ‘an apostolate of charity’. In fact, during the cholera epidemic, the action of the clergy in general was exemplary. Pope Gregory XVI, who himself was old, made visits to hospitals, thus setting an example for the clergy. We should not be surprised, therefore, that during the epidemic, the charity of Fr. Vincent Pallotti and the members of the Union emerged in a special way to assist the needy in every part of the city. Already by August 19th, Pallotti requested the ministerial faculties for the forgiveness of reserved sins for his collaborators Melia and Michettoni. He asked for them in order: “to satisfy the multitude of penitents, who in the current circumstances approach the Holy Tribunal of penance in the Church of the Holy Spirit of the Neapolitans.” (OCL II, pp.200/201) Fr. Vincent Pallotti was fully committed – among many things - to assisting the sick and helping their families and also spending many hours in the confessional. Sr. Maria Colomba (a future Pallottine Sister) testified in this regard: "Several times I have seen him [Pallotti] in surplice and stole following the hearse that carried the dead." Here is another example: shortly after the end of the epidemic, Pallotti wrote to Mr. Cassini Tommaso apologizing that he was not able to visit a certain prisoner. Mr. Cassini Tommaso had asked Pallotti to visit the prisoner in Castel Sant’Angelo (The Mausoleum of Hadrian). Pallotti could not visit the prisoner because of the other works necessitated by the epidemic. “When at last I went – writes Pallotti – the person was no longer there.” (OCL II, p.234) In order to respond to the numerous appeals that Pallotti received, he divided the city into sectors, and entrusted the sectors to the members of the Union of the Catholic Apostolate. He wrote shortly after: "In the time of cholera, The Pious Society placed a small box at the entrance of the sacristy of the Church of the Holy Spirit of the Neapolitans. And it was accessible to all the poor. It was enough that the poor person wrote in a small piece of paper the name, the surname, the place of residence, the name of the parish, and the person’s need and placed it in the box. Then, two by two, the priests went to the place of the poor and cared for their needs.” (OOCC V, 139/140) The members of the Union sought to help according to the need of the place or person; some helped with clothing and others with coupons for bread and meat; some helped bring lemons to cholera patients since lemons were then considered to be the most suitable medicine for cholera. Pallotti had noted this: “The priests of the Pious Society, night and day, went to the assistance of the cholera patients. The distribution of coupons for bread and meat had been a practice since the beginning of the Union in 1835, and continues even to this day.” (OOCC V, 139-140) At last, on October 12th, the epidemic had been contained and it was declared that the epidemic had been defeated. Rome alone reported 5,419 deaths out of the population of 156,000. Among the deaths were some people who were very close to Fr. Vincent Pallotti. One such person, Blessed Anna Maria Taigi, died of cholera on June 9th, 1837. In spite of her popularity, many medical doctors did not participate in her burial. They did so in order not to infect other people with the disease. In a letter written on June 9th, 1837, Fr. Vincent Pallotti communicated the following to Fr. Felice Randanini in Vienna: “In Rome, yesterday died in secret a great Servant of God, who had been showered with many extraordinary gifts.” (OCL II, p.183) The father of Pallotti, Peter Paul Pallotti, passed away on September 15th. He had gone to the New Church (Chiesa Nuova) to pray. There, he collapsed on the ground in front of the altar of St. Philip Neri. He was immediately rushed to his home. Even before Fr. Vincent Pallotti could arrive, he died. That same day, Fr. Pallotti dispatched three letters asking for suffrages in favor of his father "to whom I owe so much" (OCL II, 206/207) As the year 1837 ended, two other deaths marked the life of Fr. Vincent Pallotti. First was the death of Fr. Bernardino Fazzini, Pallotti’s confessor for thirty years, on December 25th (Christmas Day). Second was the death of Fr. Gaspar del Bufalo, Pallotti’s friend and collaborator, and the founder of the Missionaries of the Precious Blood on December 28th, the Feast of the Holy Innocents. A few days later, in a letter to Randanini, the Secretary of the Apostolic Nunciature in Vienna, Pallotti wrote: “Today, it has been nine days since the death of the great missionary and the canon Fr. del Bufalo, and twelve days since the death of the Chaplain of the Apostolic Hospice of St. Michael a Ripa [Fr. Fazzini]. Two great saints! Pray for me that I may gain from the examples, advices, and exhortations that they gave me with their lives.” (OCL II, 232/233) The Conclusion: The Monthly Retreat – Preparation for the Good Death: And finally, I would like to highlight a theme: the preparation for death. How many of you, today, ask yourselves about the purposes of a monthly retreat? When you do that, you will find that a monthly retreat is: · A nutritious aliment for prayer · A renewed self-dedication to God · A perfect and generous push into the apostolate · A growth in fraternal love They are all true and right, but traditionally, the monthly retreat had also been thought to be, among many other things, an exercise in preparation for death. Pallotti also speaks of it in the Rule of our Congregation. In other words, we can say that the objective of a monthly retreat is to prepare our mind and heart to face death, the undeniable reality! Firstly, we need to acknowledge it! Not just acknowledge, but we also need to overcome the fear of death. Thus, when death approaches, we will be better equipped to face it. Besides, acknowledging death would help us to appreciate our daily living by providing it with more meaning and richness. We give two examples. The First Example: It is taken from a letter written by Pallotti to a lay person, Luigi Nicoletti. Nicoletti was two years younger than Pallotti and like Pallotti, a Roman. But Pallotti had high respect for Nicoletti. Nicoletti died in 1851, just a year after St. Vincent Pallotti’s death. On September 20th, 1822 during his stay in Monte Compatri with the Carmelites, Pallotti had addressed a letter to Nicoletti. I now cite a large passage from the same letter: Yesterday, as the sun was about to set, the Spirit by the infinite Mercy of God led me on a high solitary mountain [probably the 773 meter high Monte Salomone [a mountain] that is located along the road that leads from the town of Monte Compatri to the town of Rocca Priora]. Isolated from human association, looking towards heaven, I lost myself in prayer. And as I prayed, I remembered you distinctly. In fact, God had shown me that you had not gained much from the letter that you received last year from the well-known, caring and considerate Jesuit. From the letter, it was quite frightening to know that your death was close. But it was not God’s intention that you always had the thought of death on your mind so that you lived every day as the day of your death. I humbly ask you, with my face on the ground, to promise me not to spend any day without having at least for a few moments meditated on the great Principle of Death. Do not believe that this means that your passage to Eternity is near, but I say this, so that by responding to the grace of God, you will increasingly enrich yourself with the merits for Eternity. (OCL I, pp.155/156) The Second Example: As the cholera epidemic was spreading, the anxious and apprehensive Fr. Felice Randanini, the Secretary of the Apostolic Nunciature in Vienna, wrote to Pallotti several times. He felt that he had contracted the disease (cholera). But Fr. Vincent Pallotti reassured him writing: “Look for cholera as much as you want, but you will not be able to find it because it is not for you.” (OCL II, p.139) The other times when the young secretary was caught up in fear, Pallotti eased his fear by foretelling that he would see the secretary again in Rome. Pallotti wrote: “About the fear of your death, I tell you: I wait for you in Rome.” (OCL II, p.138). Pallotti wrote another time: “Be calm: cholera will not find you.” (OCL II, p.140) The secretary, accustomed more to the diplomatic language and less to the prophetic language, wondered at the certainty with which Pallotti had spoken. Once the immediate danger was over, Pallotti asked him to humble himself and to seek forgiveness for his fears and his weaknesses in the time of distress. Pallotti wrote: “Always and in every situation, you must live and should be able to say with that spirit and with that firm belief with which the Apostle Paul said: Whether we live or whether we die, we belong to the Lord. Pray that the Lord grants me the same grace even though I am not worthy of it.” (OCL II, p.143) You, [dear friends] certainly remember these famous sayings of Pallotti: “Time is precious, short, and it never comes back. I would like that time is given a high regard. I would like to insert in the faithful the highest regard for the time.” (OOCC X, 594); “Time is precious, short and irretrievable. I would like that with the grace of God I made good use of the time like a person who had come back to life from death used it to redeem the past.” (OOCC X, 553) Dear confreres, the reactions in the face of death are varied and diverse. Some confuse awe with fear as Cardinal Ravasi said very recently, “and this is the most serious mistake one is likely to commit in this time of Coronavirus”. We need to distinguish between the fear and the awe in the presence of the Lord (‘Fear of God’). What is the difference between fear and ‘Fear of the Lord’? We can very well say that fear and ‘Fear of the Lord’ are not synonyms. “The thing I fear most is fear,” said the French philosopher Michel de Montaigne. He also defined fear as the ‘bad advisor.’ ‘Fear of the Lord’ on the other hand is ‘the beginning of wisdom’ (Prov 1:7). “Come, O children, listen to me; I will teach you the fear of the LORD.” (Ps 34:11) To describe the success of the early Church, St. Luke writes in The Acts of the Apostles: “The church had peace and was built up. Living in the fear of the Lord and in the comfort of the Holy Spirit, it increased in numbers.” (Acts 9:31). In fact, ‘Fear of the Lord’ actually brings about peace. And the paradox goes even further – ‘Fear of the Lord’ exists along with love. We read similarly in the Book of Deuteronomy: “So now, O Israel, what does the LORD your God require of you? Only to fear the LORD your God, to walk in all his ways, to love him, to serve the LORD your God with all your heart with all your soul.” (Deut 10:12) Fear, on the other hand, cannot be interwoven with love. Thus writes the Apostle John in his first epistle: “There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear; for fear has to do with punishment…” (1 John 4:18) On the contrary, ‘fearful respect’ for God is the source of great trust and thus wins over the fear. It is now up to you (up to all of us) to allow this teaching to transform each one of us personally and to transform the life of the community. To learn more about St. Vincent Pallotti, please click here. For more resources on the COVID-19 pandemic, please click here. Perhaps by this time, having become frustrated by the fact that even for a relatively short period of time we have been forced into isolation, we might find ourselves asking: “Why now?“ , “Why this bad?”, and perhaps even cursing the fact that this pandemic has so radically turned our lives upside down in what seems but a few moments. It might be an experience so taxing because it is so very different for us, but certainly not to human history. Between 1830 and 1837, a cholera epidemic swept through Europe and North America. It began in India, spread to what was at the time called Arabia, and then to Iraq. In 1831, the epidemic reached the Caucasus and soon after spread to Poland, Hungary, Portugal, France, the Netherlands, Spain, and eventually to Italy. Like epidemics in the past centuries, this epidemic also spread from city to city by way of local ports. In Rome, news of the spreading illness was met with the usual responses of apprehension and fear. But there was no small number of people who actually doubted that the disease would have a significant impact on Rome. In July of 1837, the first three people in Rome died of cholera. However, the news media denied that cholera was in fact the cause of these deaths and claimed that lies were being spread by persons seeking to cause panic and attempting to disturb the social well- being of the city. Is it not true that our initial reaction to the news of the Coronavirus was that it was far away in China and so our concern for the spread to the U.S. was rather limited? During the time of the cholera infestation of Rome, the charity of a Roman priest, now St. Vincent Pallotti, emerged in a special way. He immediately saw to it that his priests of the Congregation of the Catholic Apostolate, which he had founded, were on hand constantly (as was he) to meet the spiritual needs of the many penitents who were constantly entering the Church of Spirito Santo where Vincent served as rector to have their confession heard. Assisting the sick, caring for their families, and also spending many hours in the confessional, Fr. Vincent was extremely busy. To respond to the numerous and varied appeals he received from so many, Vincent divided the city of Rome into three sectors, entrusting each sector to his priests working in collaboration with the lay members of the Union of the Catholic Apostolate, which he had also founded, to meet the various spiritual and material needs of a then desperate people. Funds were collected and distributed to families throughout the city who had lost the person responsible for their principal source of income. The rectory of Spirito Santo became a center where families who overnight had become destitute could in writing request whatever it was they needed, and the priests with their lay cooperators would bring to the home whatever was required: bread, meat, fruit and other necessities of life as well. They found beds for the sick, redeemed articles that had been pawned out of desperation for ready cash, and helped families to pay bills that would allow them to purchase further necessities. Vincent and his priests were ever on the move, caring for the ill. They were, at the same time, finding an increasing number of children who had lost their immediate family and now had no one to care for them. In 1838, the year following the end of the epidemic, Vincent organized a lottery offering excellent and expensive prizes donated by his more affluent friends in order to raise funds to begin a program of caring for the orphans left behind by the epidemic. Many of those who won returned the prizes to Vincent that they might be sold and thereby add further monies to the orphan fund. It might well happen, as it did in Vincent’s day, that one or other of us might be called upon to meet certain needs of persons made quite helpless by the present pandemic. No one of us knows either the day nor the hour when we might run into a situation that calls for immediate involvement and appropriate response with no questions asked. May the life of St. Vincent Pallotti, who prayed that “the work of the Blessed Trinity be realized in us,” be a model and inspiration for us during this time. Cf St. Vincent Pallotti: Prophet of a Spiritual Communion. Ed. Fr. Francesco Todisco, SAC. Trans. Kate Marcelin- Rice. Herefordshire, United Kingdom. Gracewing, 2015 3/30/2020 The 14 Holy Helpers: Turning to the Saints During the Coronavirus | COVID-19 ResourceRead NowThe other day I drove past a grocery store that had people waiting in line to get inside and stock up on food and other supplies due to the continuing spread of COVID-19. Most of us have seen pictures of empty store shelves devoid of food and medicine as people make a mad rush to make sure they have what they need to self-quarantine for an extended period.

An equally startling yet vastly different image is that of empty church pews during the numerous Sunday Masses being livestreamed from Catholic parishes around the world. Whereas the emptiness of store shelves suggests the preparedness, albeit over the top at times, of consumers, the emptiness of Church pews suggests the possibility of the Christian Faithful not having the spiritual support which they need during this pandemic. Fortunately, the Church has been through pandemics before, and an examination of our past offers insight for our days ahead. At the outset of the Bubonic plague, commonly referred to as the Black Death, Europe’s faithful sought heavenly aid to withstand the suffering caused by the plague. Various communities invoked the Blessed Mother and the saints for protection against the plague. One of the most interesting and enduring of such devotions comes from Western Germany where 14 “auxiliary saints” were venerated together as the Fourteen Holy Helpers. The Fourteen holy helpers were:

Pious legend tells of a shepherd boy receiving a vision of the 14 Holy Helpers in a field near the German town of Bad Staffelstein. After this, a church was erected on this spot and miraculous healings began to occur on account of the intercession of the Holy Helpers. A shrine church still stands in Bad Steffelstein to this day where pilgrims continue to go and seek the help of the Fourteen Holy Helpers. As this group devotion spread to other countries, new helpers were added for more popular saints in any given region including St. Nicholas, St. Sebastian, and St. Rocco (Roch). Regardless of which saints composed the group of helpers, the people of Europe implored the Helpers’ aid against the harsh symptoms of the Black Death. Today, the world once again suffers from a pandemic, the outbreak of the novel Coronavirus. Though medicine and science have surely advanced and we know much more about diseases and how they spread than medieval Europeans, maybe those Christian faithful of the past can teach us an important lesson: the lesson of faith and trust in God. As we adapt our lifestyles to work from home, social distance ourselves, and view Mass via livestream, let us not forget the great cloud of witnesses who watch over us from heaven. May we turn to their help during these challenging times. Fourteen Holy Helpers, Pray for us! Joseph Basalla is a graduate from The Catholic University of America living in the Washington, DC area. In the movie The Farewell, the central plot hinges on the question of an individual vs. communal approach to the burden of end of life care. One of the central characters has cancer, and the issue surrounding the family is whether the person with the disease should know or not. In the US, as the movie acknowledges, such duplicity would not be likely to happen, but in China, where the movie takes place, society often allows for such things because they believe the burden of suffering is to be carried by the family and friends rather than the sick or afflicted. I found that to be a fascinating concept because most of us have experienced the loss of someone due to cancer, and the question of death and mourning is a very present concern to all of us. I would recommend viewing the movie, if for nothing less than to understand the potential hardships of walking with someone who is about to die and with those that love them. Our faith acknowledges that our time on earth is not all that there is, but rather that we are made for heaven and joining God. The Catechism of the Catholic Church declares: “The Christian funeral is a liturgical celebration of the Church. The ministry of the Church in this instance aims at expressing efficacious communion with the deceased, at the participation in that communion of the community gathered for the funeral, and at the proclamation of eternal life to the community (CCC 1684).” As Catholics, we believe that there is life after our life on earth. So the funeral and death itself serve as reminders of the Paschal Mystery and our hope for all—and in particular, those who have just died—to have eternal life in heaven with the Lord. The prayer spoken while receiving ashes on Ash Wednesday is a poignant reminder of this: “Remember you are dust and from dust, you shall return.” Time on earth is fleeting, but time in heaven is eternal. As Catholics, we are part of a community of believers. We must not only accompany the one who is preparing to die, but also those who the deceased is leaving behind. This is not the responsibility solely of the priest or deacon presiding over the funeral rites, but rather a shared responsibility of all the church. The Catechism goes further to explain that funeral ceremonies have the Eucharistic Sacrifice as a critical component because: “It is by the Eucharist thus celebrated that the community of the faithful, especially the family of the deceased, learn to live in communion with the one who ‘has fallen asleep in the Lord,’ by communication in the Body of Christ of which he is a living member and, then, by praying for him and with him” (CCC, 1689). It is essential as a community of faithful to also accompany those left behind who are grieving the loss of a loved one. This grief is normal and completely human, but it means that we need to accompany those grieving and serve as a living reminder of Christ’s presence in their lives. We are called to serve as witnesses to those we encounter daily, whether we know them well or not. As stated in the book the Art of Accompaniment: Theological, Spiritual, and Practical Elements of Building a More Relational Church: “Witnessing can be effective even if a deep, committed relationship is not yet formed…witnessing demonstrates an example of an integrated Christian life within the one who witnesses. … Witnesses are essential to the process of spiritual accompaniment because, ‘modern man listens more willingly to witnesses than to teachers, and if he does listen to teachers it is because they are witnesses (Evangelii Nuntiandi)’ (Art of Accompaniment 16)” Times of suffering and hardship are especially profound moments for evangelization and witness. As a Church, we can offer hope and healing to those who are dying or grieving the loss of a loved one. For more resources on Accompaniment, please click here. “Who did you pick as your confirmation Saint?”

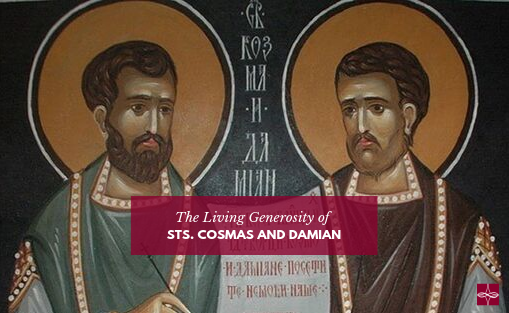

“St. Vincent!” “Oh cool, St. Vincent DePaul, that’s great!” No…not him…St. Vincent Pallotti…” “Who is that?” The name game for saints with common names is a frequent and sometimes frustrating occurrence, as is often the case with St. Vincent Pallotti—my patron, confirmation saint, and friend. Pallotti was many things: the friend of popes and cardinals, confessor of many of the religious in Rome at the various colleges, and great supporter of the laity. Throughout his 55 years of life, Pallotti did everything for the infinite glory of God (infinitam Dei gloriam). His life, message, and charism were life-giving and meaningful while he was alive, as well as today. Many saints can seem out of our reach—St. Joseph of Cupertino is known for flying and St. Padre Pio of Pietrelcina received the stigmata. While there are accounts of St. Vincent Pallotti levitating and bilocating, his life and legacy are not marked solely by these acts of mysticism. One of the main reasons that Pallotti’s example resonates so deeply with me in 2020—170 years after his death—is because of how humble and “normal” his life was. Now, “normal” is quite relative, but in comparison to many well-known saints, Pallotti’s life was normal, even boring. Pallotti’s parents were devout and his love for Christ and the Church was evident from a young age. There are many stories of St. Vincent’s great care for the poor, including a story of him giving away his bed to a beggar. St. Vincent was not a particularly good student as a young boy, and it was not until his mother prayed a novena to the Holy Spirit for his education that Pallotti became a model student. As a priest of the Diocese of Rome, Pallotti spent much of his time hearing confessions. After a cholera epidemic struck Rome in the mid-1800s, Pallotti founded a home for orphaned girls. He set up night schools so that working men could receive an education. He was also a mathematician. In fact, it was in his study of calculus that he came to understand God as Infinite Love. There was no deed too small, no task unworthy of his effort. To the 2020 Catholic Church in the United States, Pallotti’s great interest in collaboration with and co-responsibility of the laity might not seem outrageous, but in the 1830s and 1840s in Rome, it was. Many of Pallotti’s closest collaborators were lay people, one of whom was Blessed Elisabetta Sanna. He also made sure that the various ministries and apostolates that he established involved the laity not just as pawns or placeholders, but as central actors in the life of the Church. St. Vincent Pallotti can teach us so much. He struggled greatly with anger and pride; in this we learn that we are not alone in our personal struggles. He lost many of his siblings when he was young; in this we learn that we are not alone in our loss. He turned people’s attention to God when he distributed pamphlets during the Roman carnival, or when he would drop a reliquary from his sleeve so that the Romans who would come to kiss his hand (as was customary to do to priests at the time) would kiss it instead of him. In this, we learn that we too can persevere when the world around us tells us things that are contrary to what we believe. I learn from St. Vincent Pallotti every day. He is a model for me in perseverance, humility, and devotion to God. When I sin and fall, I remember his personal reminder that he was but “nothingness and sin.” When I look at the apostolic works that I take part in, the ones that are looked down upon or seen as unrealistic, I think back upon Pallotti and the same judgements that many must have made about him. The greatest influence that St. Vincent Pallotti has had on me is the image of God as Infinite Love—that Infinite Love can love me at my best and my worst. The Infinite Love of God is what balances the scale with sin on one side and being the beloved of God on the other; it reminds us who God is in his greatest depth. My life and my faith have been so greatly touched by St. Vincent Pallotti and I am deeply thankful for him. May he continue to intercede for us all and may we, as we undergo our apostolic works, look to him as a mentor, a guide, and a dear friend. St. Vincent Pallotti, pray for us. To learn more about St. Vincent Pallotti, please click here. As we celebrate the third World Day of the Poor, prophetically established by Pope Francis, I have just returned from a very unique visitation to Columbia and Venezuela. Let me limit myself here to Venezuela, because of some very touching experiences in this country. Venezuela, as we all know, is one of the resourcefully rich countries of the world, blessed with Petroleum, gold, and many other precious minerals. In the 1960's, this was one of South America’s wealthiest countries, enjoying the highest standard of living; yet today, how different the situation. 1 US dollar is equal to about 30,000 Venezuelan Bolivar. The monthly earnings of a worker is around $5; a medical doctor told me he gets $20 per month, if he even comes to be paid. Just imagine, then, the situation of ordinary people. Millions are migrating to all parts of the world. If possible, the able bodied men and women escape the country, leaving behind their parents and grandparents. People die not because they cannot be healed, but for lack of ordinary medicines; medicines which are either unavailable, or people are too poor to purchase them. One woman I met was suffering from skin cancer and heart problems; she can do nothing. This is a true story. Just imagine her plight. For lack of money or limited transports, children and teachers are unable to go to school. While there are many more examples to narrate, my intention is not to show this wonderful country in a bad way. Paradoxically, despite all of these hardships, I found the people very affectionate and joyful. I met with so many pastoral groups working in the parishes, and hardly anyone spoke about their hardships, or asked for any sort of help. The people were so nice, and I was really touched by them. Through Caritas Poland and local aid, our parishes are organizing soup kitchens and many other charitable activities together with the parishioners. As a small contribution from We Are A Mission, I myself went around distributing food items in one of our parishes. It was a very touching experience. Pope Francis speaks much about the poor, migrants, and the culture of indifference. At times, people get annoyed; why does the Pope keep harping over the poor? The question is precisely what he posed to us in his homily: “do I have at least one poor person as a friend in my life?” Have we come face to face with this poverty in our lives as Christians, or are we merely experts on speaking about it; limiting ourselves to words, and not truly encountering this existentially dark reality? Again as the Holy Father has written, “let us set statistics aside: the poor are not statistics to cite. The poor are persons to be encountered; they are lonely, young and old, to be invited to our homes to share a meal; men, women, and children who look for a friendly word.” Those who lived through the Second World War in Europe will know what it means to survive during and after, yet their grandchildren may not even like to read about those days anymore. It is one thing to speak about poverty, but it is something altogether greater if one has had a real taste of it. When Venezuela- a country greatly blessed by God with all the necessary riches for a decent living- is reduced to such a level of inhumanity by fellow human beings, can we remain indifferent as though it is only their problem? It’s as good as saying that the Amazonian issue is something of only a few countries of that area. But devoid of Amazon, the rest of us would be gasping for oxygen! When a family with a couple of small children wake up in the morning with neither food nor money to purchase it, how will the parents control the weeping kids? When some worry over their health due to overeating, having to count calories after all of the food they consume and walk for hours after they have eaten, it looks so absurd and paradoxical that millions elsewhere starve to death. This is the naked truth that makes us feel uncomfortable. Many will wash their hands and say that it’s all because of corruption or political anarchy in these countries. That is all true. The sanctions that many countries impose to correct these unjust structures and systems will end up hitting the poorest of the poor, and not those at the top, is another truth. I am not writing these lines with the hope of solving all the world’s problems. Instead, it’s to show that the poor are the blessed. The poor find their ultimate trust in Yahweh when all other sources of security are vanish. These are the people blessed with a genuine sense of humanity and compassion, as true evangelical joy is found in poverty and simplicity of life. The Lord of the Universe, Master of our History and Destiny, will make the necessary corrections and justice at the end. Until then- like Sunday’s Gospel- patience and perseverance in our trust in HIM, and the goodness in each person, must prevail. The best comes out of us when we are cornered to such a level. The more efforts there are efforts to destroy our humanity and dignity as persons, the greater will be in the interior force to manifest the beauty of freedom and preciousness imprinted upon us as an image and likeness of God. As we celebrate World Day of the Poor, let us unite ourselves with our Holy Father; kindling a candle of hope for the suffering parts of the world, be it through a smile, prayer, or even a dollar. Who knows, tomorrow we might need them, as this is so much part of our human condition. It is no wonder, then, that the Son of God Himself chose to be born poor to make us rich in divine blessings. “The poor save us, because they enable us to encounter the face of Jesus Christ.” Today is the optional memorial of Sts. Cosmas and Damian, who were twin brothers born in the third century in Arabia. Both Cosmas and Damian became physicians, and in true Christian charity, refused to accept payment from their patients. During the persecutions under Roman Emperor Diocletian, the brothers’ renown in their Christian community made them easy targets. They were imprisoned and tortured by various means in an effort to force them to recant their faith, and after surviving most of these tortures while remaining true to Christ, Cosmas and Damian were finally beheaded.

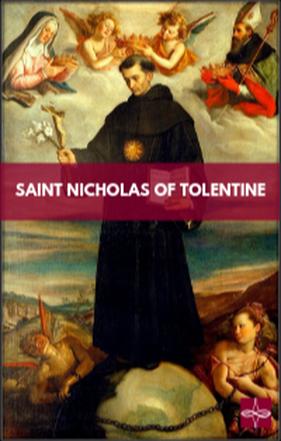

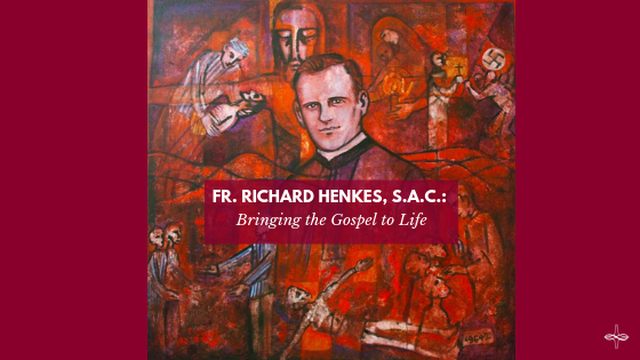

What draws me to the story of Sts. Cosmas and Damian is not only their adherence to the faith while under excruciating torture, but also their unfailing generosity to those around them. They tended the sick in their community and did so without asking for or taking any monetary compensation. I like to think this was because they were often helping sick people who were also too poor to afford a physician in the first place. Generosity is a virtue that can easily be motivated by pride—we do good things for others, secretly hoping to get accolades or some kind of reward for being so self-giving. But I think generosity is really about giving to others —material, spiritual, or emotional—because you know the other will benefit, even if there is no compensation for you in return, or if (like Cosmas and Damian) you refuse to take any. Generosity is not only exemplified by a wealthy man donating money to charitable causes, nor only by going on mission trips to help those in poverty, nor is it demonstrated by showering poor children with gifts at Christmastide. We can cultivate the virtue of generosity in ourselves much closer to home and on a daily basis—just as St. Cosmas and St. Damian did. Generosity is lived out by a talented musician volunteering at his church to worship God in song, or by a mother who prepares and brings home-cooked meals to other families in her parish who have a new baby or have had a recent surgery. There is also spiritual and emotional generosity: being present and available to our siblings, children, parents, or friends as they struggle with transitions or discernment. When we engage in these acts of generosity, we serve Christ by serving others—even if it is not necessarily a sacrifice for us to do so. (Although I know for myself, the sacrifice that comes with being generous is striving to be selfless in my generosity and not to expect or desire reciprocation.) We are called to use anything that we have been given in order to glorify God. And what about those—presumably poor—people that Sts. Cosmas and Damian healed and treated? Who knows what kinds of generosity they were able to offer to their benefactors as a result of their encounter with the twin saints? Maybe they were generous in their prayer lives and interceded for the physician brothers. Maybe they were inspired by the generosity and faith of the two saints and went on to assist others in their community. Even if we cannot always be materially generous to each other, giving of ourselves in any capacity can cause a ripple effect of generosity throughout our communities. We can also learn to support and foster the generosity of others by thinking about how we respond when we are offered someone’s generosity, whether we asked for it or whether it was volunteered to us. Personally, I am working on asking for help or accepting generosity with humility. I know that I am less likely to help someone if they repeatedly protest my efforts or insist that I am doing too much, and therefore I try not to protest or downplay the good work that someone does for me. I try to remind myself that by serving each other, we are ultimately serving Christ. Questions for Reflection: Have you ever been the recipient of an act of generosity that changed your life? How so? My own faith journey has been greatly influenced by the Augustinians – a religious order of friars, joined by seculars and friends, who follow the Rule of St. Augustine. Simply put, Augustine’s Rule invites men and women to “be of one mind and heart on the way to God… [to be] travelers on pilgrimage together, wherein Christ is our constant companion, as well as our way and our goal.” St. Augustine of Hippo is one of the best-known saints in the Catholic Church. Although he was born in the 4th Century, his writings—like Confessions and The City of God—continue to inspire spiritual seekers to this day. For his contributions in theology, Augustine is also considered a Doctor of the Church. Beyond these accolades, Augustine’s personal character and self-proclaimed “restlessness for God” have inspired numerous men and women to take up his search for truth. One of these people is St. Nicholas of Tolentine, whose feast we celebrated on September 10th. Growing up in an Augustinian parish in Staten Island, NY, I knew there were at least a few saints from the Augustinian family, including: Augustine’s mother, St. Monica; St. Rita of Cascia; St. Thomas of Villanova (there’s a basketball-loving university named after him!); and St. Clare of Montefalco. I also knew of a church in the Bronx named St. Nicholas of Tolentine, but I must admit, I knew very little about him. A few years after college, and after some time away from my family parish, I found myself in a state of constant restlessness and spiritual doubt. Desiring a change, I reconnected with my past by joining the Augustinian Volunteers, a year-long volunteer program in which I traveled across the country, lived in intentional community, and learned about the greater Augustinian family. This experience confirmed a special place in my heart for the Augustinian saints, and I have been pleased to learn more about this man Nicholas who “sought for God by means of a deep interior life… [and] the practical love of neighbor.” According to a brief biography, Nicholas “was a simple priest and Augustinian friar who touched the lives of many.” Born to a poor family in Italy in the year 1245, Nicholas became an Augustinian friar at an early age (likely 16 or 18) after being inspired by another Augustinian preacher in his hometown. The Augustinian history states Nicholas was “full of charity towards his brother Augustinians as well as towards the people to whom he ministered. He visited the sick and cared for the needy. He was a noted preacher of the Gospel. He gave special attention to those who had fallen away from the Church. People considered him a miracle worker.” Nicholas fasted often and received visions during his lifetime, including that of angels repeating “to Tolentino,” where he moved and worked for the remainder of his life. In the tradition of Augustinian hospitality, Nicholas is said to have been over-generous in his duties feeding the poor at his monastery; so much so that his superiors asked him to hold back a bit. Nicholas (like many medieval saints) is linked through legend to miraculous incidents involving food. Once after weakening himself through prayer and fasting, he had visions of The Blessed Virgin and St. Augustine imploring him to eat some bread marked with a cross and dipped in water. This bread immediately regenerated his strength, and he went on to give the same bread to the ill while invoking Mary – thus beginning the Augustinian custom of distributing Saint Nicholas Bread. Another legend, perhaps inspired by contemporary Franciscan values and love of animals, tells of Nicholas vowing not to eat meat the rest of his life. When served a roasted fowl, Nicholas prayed and the bird returned to life, flying away from the table. Nicholas died on Sept. 30, 1305, and was canonized by Pope Eugene IV (also an Augustinian) in 1446. He was the first Augustinian to be canonized. At this ceremony, Nicholas was credited with about three hundred miracles. St. Nicholas is typically depicted in the black Augustinian habit, often with embroidered stars or a sun emblazoned on his chest, which seems to point to the great quote from his inspiration, St. Augustine: “Men go abroad to wonder at the heights of mountains, at the huge waves of the sea, at the long courses of the rivers, at the vast compass of the ocean, at the circular motions of the stars, and they pass by themselves without wondering.” In these days in which so many of us are searching for answers, let us pause to remember a kind saint who encouraged patience and prayer as ways of knowing and being. To learn more about faith-based service, please click here. How can we implement the Gospel? Although this is a difficult question, it is a very important one to answer. For us Christians, it is not enough to hear the Gospel. We are called to put it to action in our own life. Sometimes it is difficult to take action. How should one do it? The good news is that we are not alone in answering this question. We have examples of many who have asked it themselves and used their lives to answer it. Every time the Catholic Church declares a person blessed or a saint, she gives us an example of how the Gospel can be lived. Blesseds and saints are role models for our faith journey. Even if every one of us has to find out individually what God is calling us to and how to live the Gospel, the blesseds and saints can help us learn how to answer this call. How can the soon-beatified Pallottine Father Richard Henkes, S.A.C. be an example for our life and for our quest for God? When I read Fr. Henkes’ biography, I learned that he tried to live out the Gospel even when it seemed inconspicuous and less effective. Three situations in his life illustrate this. The first event took place when Father Henkes was a teacher at a Pallottine school. At this time, Nazi idealism had become stronger in Germany and ultimately reigned the country. Father Henkes saw the faith as a guide for young people who were confronted with the race theory that claimed the superiority of one people over others. Father Henkes knew that even small actions could have a big impact, for better or for worse. As a teacher, he gave the whole class a punishment for laughing at a child who used a Czech word; at this time, the Czech language and the Czech people in general were looked down upon. This might be a small incident, but Father Henkes saw it as his responsibility to intervene for the rights of the child and for the equality of human beings: he used his position as a teacher to go against inhumanity and injustice and brought the Gospel to life. Furthermore, Father Henkes used his work as a pastor to combat injustice. In his homilies, he spoke clearly against the Nazi ideology and their contemptuous acts, and he even got several warnings from the authorities about his preaching. In 1935, Father Henkes had confrontations with the Gestapo (secret state police) because he said in his sermon that the Nazi image of humanity was wrong. He knew that, if he continued, the government would prosecute and punish him. Though he may have been afraid, he did not stop because he was sure that he had to say and do whatever was possible against the Nazi regime. In his eyes, it was not right to stay indifferent to inhumanity, injustice, and murder, and to believe at the same time in God and God's infinite love for all people. Therefore, he continued to criticize the Nazis in his homilies, to speak publicly, and to encourage the people who agreed that the Nazis were wrong. Because of this, Father Henkes got arrested and deported to the concentration camp in Dachau. Finally, once in the concentration camp, Father Henkes also cared for the sick. When the war was almost over and the concentration camp was close to being freed, a typhoid epidemic broke out. Father Henkes volunteered to care for the infected people, most of them Czech. He did not have to. He was not forced to do it and he willingly experienced the inhumane conditions because he saw the care of the sick as his duty. It is clear that he lived the Gospel in the concentration camp: he brought a little bit of humanity and compassion into that hellish place. Father Richard Henkes is a role model for me because he was moved by God in such a way that the Gospel poured out into his daily life. He did not wait for a big opportunity to preach the Gospel; he did what he could in particular moments of his life. He did not stop hate after he punished the class in the school where he taught. He did not prevent or stop the war by preaching against the Nazis. He did not free those in the concentration camp by caring for the sick. But I really believe that he brought the Gospel and the Kingdom of God to people around him in every one of these incidents. He cut the circle of cruelty for the one pupil in the school, his parishioners, and the sick in the concentration camp. Not all of us are a teacher, priest, or nurse. But all of us are called to do what is needed in the situations we are given, according to our capabilities. In doing so, the Gospel will become reality. To learn more about the beatification of Father Richard Henkes, S.A.C. please click here. “Come away by yourselves to a deserted place and rest a while.” (Mark 6:31)

The Apostles had been sent out by Jesus and reported back all that they had done (Mark 6:30). He knew that they needed to care for themselves, so they set out in the boat to go and rest. But, what did they find when they arrived? Over 5,000 people waiting to be fed both spiritually and physically. Despite their probable fatigue, they continued to minister to the needs of the crowd. Their rest was not long, but they did have time together in the boat away from the crowds. They also rested in the Lord as he spoke to them and the crowds. Self-care, therefore, does not mean long periods of time, but that which is needed to move us into fuller service for Christ. When moments of self-care such as prayer, study and spiritual reading, appropriate times of rest and relaxation, or time with friends and family are neglected, living as an apostle who accompanies others into deeper life in Christ can become challenging. Self-care is not self-focus; it is not self-serving. Very often caregivers, especially of the elderly or infirmed, become ill themselves because they have not set apart time for self-care. It is understandable. They want to give fully to their loved ones. Those in ministry or the apostolate want to do the same for the beloved of Christ. In both instances, though, great damage can come to the caregiver—leaving them unable to care. Self-care is meant to assist in becoming more other-focused, more self-giving. In many ways, the great founder of Western monasticism, St. Benedict, whose feast day is today, understood well what is at the heart of Christian self-care – ora et labora – prayer and work in the context of a stable community life. When either are neglected, then one is not able to give fully for the Lord. Life in community, whether in a religious community such as a monastery, or in the community of faith, gives one a stable place to be accompanied, to grow in the spiritual life, and to rest with Christ, especially in the Eucharist. Relationships can be built in trust and burdens can be shared. Peace that comes from the Prince of Peace can then be found. It is this peace, love, and mercy that we share with others as his apostles. In the last months, a former student of mine discerned that he is called to live as a Benedictine, another discerned that he is called to the Dominicans, another as a diocesan priest, and two others that they are called to marriage. Prior to these decisions, there was much prayer, but also a bit of a lack of inner peace. Accompanied by many, these young adults came to peace in their decisions as their way to follow Christ as his apostles. Please pray for them. Pray also for those, especially in ministry and apostolate, who are not properly caring for themselves. May we accompany them to care for themselves so that they may better care for the People of God. May the Charity of Christ urge us on! For more resources on Self-Care in Ministry, please click here. Two forces have particularly influenced my life. The first is my Catholic faith – given by my parents and nurtured by others as I grew. The second is my adulthood experience with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). In wrestling with both of these forces (at times feeling like Jacob, who wrestled with God), I accidentally discovered a saint whose experiences reflected my own. Saint Dymphna lived in Ireland during the seventh century, after the time of Saint Patrick, Saint Brigid, and Saint Columba. Christianity was practiced by many – including Dymphna’s mother, who had her daughter secretly baptized. Dymphna’s father was a pagan king named Damon. Dymphna’s mother died when Dymphna was just 15 – throwing her father into a terrible grief. Damon’s counselors advised him to remarry, and though they searched for another wife, they found none. They then advised Damon to marry his daughter, who reflected her mother’s great beauty. Initially repelled, Damon eventually agreed and proposed to his daughter. Under the guidance of her confessor priest, Saint Gerebran, Dymphna rejected her father’s proposal, and fled Ireland for Belgium. Tradition states that Dymphna then built a hospice in Geel for the sick and the poor, where she remained for some time. Soon, Damon and his men traced Dymphna’s journey, and ascertained her whereabouts due to Dymphna’s use of foreign currency. Confronted by the mad king, Saint Gerebran rebuked his behavior, and Damon had his men kill the priest. Still hoping to win his daughter, Damon then pleaded kindly, offering wealth, prestige, and honor. Dymphna, steadfast in her vow of chastity, rejected the offer – and by her own father’s sword was beheaded. Soon after Dymphna’s martyrdom, several “lunatics” spent the night in the countryside where Dymphna died, and woke up in the morning healed. This miraculous place became known throughout Europe: a church was eventually built in the 1300s, with a sanctuary expansion built to accommodate pilgrims seeking mental relief. Townspeople themselves even began taking them into their homes, a tradition that continues to this day. Saint Dymphna entered my own life in a chance way seven years ago, near the onset of my OCD symptoms – which involved uncontrollable obsessions and time-consuming “checking” behaviors. Around this time, I discovered in my bedroom a prayer coin invoking Saint Dymphna. I do not recall where this coin came from – and I certainly had never heard of Dymphna before. But the prayer on the back captured me: “Oh St. Dymphna, Patroness of nervous and mental illnesses, grant that, through prayer, I may be pure in mind and soul.” Fascinated by her story and her Irish identity, I began to read, learn, and ask in prayer for her help. This relationship deepened and developed into my own pilgrimage to St. Dymphna’s church in Geel – which was closed when I reached Belgium! Nevertheless, she has continued to inspire my journey from OCD sufferer to OCD advocate, and I am more convinced than ever that she is a great intercessor and resource in our current Age of Anxiety. Below are some brief meditations on Dymphna’s continued influence on my life: 1. Dymphna kept faith even in grief. We all know how grief challenges our faith. Not only did Dymphna lose her mother, but she also had to tread the impossible tightrope of consoling her father while recognizing that his sickness was warping him. This must have torn at Dymphna’s heart. Yet even amidst suffering, she did not stop hoping in God’s providence. In my own life, losing my brother six years ago in an accident severely challenged my faith in God. During this time, I believe Saint Dymphna’s help guided me back to a place of trust and hope. 2. Dymphna chose the path of unknowing and vulnerability. By fleeing to Geel, Dymphna took a major-league risk and rejected the familiarity of her native land. Yes, she was momentarily safe from the king – but incredibly vulnerable as a foreigner and refugee. In many ways, staying home and appeasing her father would have been the “safe” choice. OCD constantly tempts me with gaining “safety” at the cost of doing ridiculous compulsions. While it’s terrifying to reject what OCD wants me to do (“Think hard enough and you’ll have peace!”), I have to respond by saying, “I’m willing to be anxious and unknowing, so I can live a real life.” That Dymphna, Patroness of mental illness, was beheaded, indicates to me that I must abandon relying on my brain, and embrace God and that which I cannot see or “figure out.” 3. Dymphna perfected her own authority and freedom to choose. In standing up to Damon, Dymphna inspires all of us who face temptation and all who face oppression from those who misuse their power. Not only did Dymphna preserve her vows of chastity, but she also avoided another, potentially graver misstep – the acceptance of a false crown, that is, her mother’s rightful crown. The choice to be independent is terrifying. The story of Dymphna, however, shows true independence is possible, through faith in God who desires our freedom from sin and from oppression. With God’s help we may learn to abandon the perceived “safety” of acquiescing to the soul-stealing machinations of tyrants (even the tyrants in your own mind), at which time the opportunity for freedom, originality, generosity, charity, and creativity arises. Questions for Reflection: What false crowns have you been offered in your life? What powerful proposals have been extended at the cost of your authority and freedom to choose? The authentic Christian life resounds with love. Beyond any fleeting attraction or fondness, this love is not meant to be hoarded, but to be given in charity and service to others. The love of a Christian reflects the love of God, without Whom we would not exist nor would we have the capacity to love beyond the other, lesser creatures of this planet. This love cannot be restricted to a single day on the calendar but is meant to flow freely every day at every hour through every difficulty and joy, every sorrow and labor, and every moment of pain and peace. It is love which motivates us not only to live for others, but always for the glory of God.