|

Thank You, Lord, for Socks

Before Thanksgiving meals at my grandparents' house in Cincinnati, we participated in a special Thanksgiving grace. This prayer was based around the invitation to have everyone "go around the table and say something you’re thankful for.” In this situation and others like it, I became stressed out by the pressure to come up with “something good” – i.e. some prayer that makes me seem adequately grateful to God in the ears of those I pray with. Therefore, I try to avoid being the first person to offer to the room the reason for which I'm grateful. I need time enough to think of something esoteric; something that justifies to my family or friends the amount of time I have spent in post-secondary theological studies; something that gives evidence of a decent prayer life; some prayer that shows that I have recognized God's work in a place where not many may have recognized it. As long as I'm given enough time before the table gets around to me, I might show my "advanced spiritual depth" by deciding to give thanks to God for something like "the ability even to give You gratitude, which is sourced in You." Of course, the pressure to give thanks for a "smart" reason is entirely self-imposed, and fairly egotistical. G.K. Chesterton, an author noted for his joy and sense about the world God gave us, offers us this practice to chew on: “You say grace before meals. All right. But I say grace before the concert and the opera, and grace before the play and pantomime, and grace before I open a book, and grace before sketching, painting, swimming, fencing, boxing, walking, playing, dancing and grace before I dip the pen in the ink.” There's no word on how complex Chesterton's "grace" is, and I imagine it's simple enough that spoken words may not always be necessary... a breath of gratitude. Children are more likely to practice this sort of gratitude than adults, which is probably one reason why Christ says we should be more like them. It's the "silly" things, the gifts spoken by the smallest children in these table prayers, which are endearing and ultimately demonstrate the right conception of gratitude - a child saying "Thank you, God, that I get to wear my favorite socks today." I could have legitimately said "thank you" in this prayer for anything that popped into my head. My socks are also gifts from God, and I may rejoice in them. Sure, it is good to take the time to step back and reflect on what areas of God's gifts we may have recently missed in our lives. It is not a bad thing to realize that even our ability to give thanks to God comes from the free will he has bestowed upon us. However, remembering to give glory to God for whatever we happen to be doing at this moment is an even better spiritual habit. Do me a favor and read Psalm 136 today, which ends, "Give thanks to the God of heaven, for his steadfast love endures for ever." Happy Thanksgiving. Laura Berlage serves as Director of Religious Education for Incarnate Word Parish in the Archdiocese of St. Louis.

0 Comments

They came to Capernaum and, once inside the house, he began to ask them, “What were you arguing about on the way?” But they remained silent. They had been discussing among themselves on the way who was the greatest. Then he sat down, called the Twelve, and said to them, “If anyone wishes to be first, he shall be the last of all and the servant of all.” Taking a child he placed it in their midst, and putting his arms around it he said to them, “Whoever receives one child such as this in my name, receives me; and whoever receives me, receives not me but the One who sent me.” – Mark 9:33-37

Here, we have another classic example of Jesus’ disciples screwing up. I love them for that. In my struggle to figure out how I can better receive Christ, the knowledge that these great saints also constantly screwed up keeps me from spiritual perfectionism, and instead lets me focus on growth. In this particular case, the disciples failed to discern that concern for the welfare of others needed to trump their own ambition. In my circles of Catholic emerging adults, we talk a lot about discernment, and there is an ever-growing area within practical Catholic spirituality about how to practice discerning well. We discern marriage or religious vocation; we discern where to begin a job search; we discern whether even to begin that job search or go on for more education. We discern our roles within changing friendships. It’s so common that among my friends, discernment is even tossed around as a joke, such as when we “discern” whether we should order another pizza for the game watch party. However, what struck me in this Gospel passage is the fact that the disciples clearly had to practice something else before moving on to discernment. The prerequisite to discernment must be a well-formed conscience. The disciples had no idea what they should have been talking about along the road, but they were ashamed when Jesus asked what their conversation was – they knew, deep down, that who was the greatest among them certainly wasn’t a question worth their consideration. Was that gut feeling present when the conversation started? The Catechism of the Catholic Church §1779 explains the need for introspective vigilance, and quotes the advice of St. Augustine: It is important for every person to be sufficiently present to himself in order to hear and follow the voice of his conscience. This requirement of interiority is all the more necessary as life often distracts us from any reflection, self-examination, or introspection: “Return to your conscience, question it… Turn inward, brethren, and in everything you do, see God as your witness.” (Saint Augustine) If we are truly going to discern as often as we profess about matters great and small, we need to attend to this interiority. Prayerful discernment, or choosing between good things, is hard enough. It becomes much harder if you can’t see what is not of God and can’t rule that out immediately. Today is the memorial of Teresa of Avila, a great contemplative. She certainly believed that when you don’t distract yourself with things that aren’t worth filling your mind, that’s when you can hear God. In Teresa’s meditation on the Song of Songs, she warns her religious sisters against “false peace” with oneself - a “peace” that anesthetizes and atrophies the soul. She took the time to identify nine kinds of false peace, which can stymie our growth into the disciples that God created us to be and which Christ calls us to be. We are each like the disciples in this Gospel: imperfect, but called by Christ to recognize when we could have done better. When we recognize the wrong questions, we can begin to discern which are the right ones. The disciples didn’t remain at peace with their pride, and grew into some of the greatest servants of others. For myself, I pray that I can stay away from the false peace that would make me complacent with the children and adults whom I serve as a parish director of religious education. Lord, help me to receive You in them. Laura Berlage serves as Director of Religious Education for Incarnate Word Parish in the Archdiocese of St. Louis. “Do not worry about how or what you are to speak in your defense, or what you are to say; for the Holy Spirit will teach you in that very hour what you ought to say.” - Luke 12:11-12

“Moses, however, said to the LORD, ‘If you please, LORD, I have never been eloquent, neither in the past, nor recently, nor now that you have spoken to your servant; but I am slow of speech and tongue.’ The LORD said to him, ‘Who gives one man speech and makes another deaf and dumb? Or who gives sight to one and makes another blind? Is it not I, the LORD? Go, then! It is I who will assist you in speaking and will teach you what you are to say.’" - Exodus 4:10-12 I wouldn’t necessarily go so far as to characterize myself “slow of speech and tongue” as Moses does, but I do face certain insecurities when it comes to speaking out (about the faith or any topic). I am a perfectionist. I often hold back from evangelizing out of fear that I will say the wrong thing, or even the right thing but not do it justice. This fear is the reason I prefer writing; I can revise until the text says (almost) precisely what I want. However, I am finding more and more that I am being thrown into situations which do not have space for revision. How can I be sure to respond in a way worthy of my baptismal call? When we volunteered together on a recent Confirmation retreat, my friend gave an eloquent reflection on the person of the Holy Spirit as a gift and an advocate to us and for us. The gifts of the Holy Spirit - including those which precede eloquent speech, such as knowledge and understanding - are truly the gift of the Holy Spirit, the person of the Trinity. We are given God, whom we can call to our side to provide us with whatever strength we currently need... even when we’re unsure what we truly need. St. Paul points out that “we do not know how to pray as we ought, but the Spirit itself intercedes with inexpressible groanings” (Romans 8:26). My friend, who is a high school teacher, found that on the days when he remembered to pray to the Holy Spirit before class, the class had the most fruitful discussions. University of Notre Dame President Emeritus and civil rights champion Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, repeats the simple prayer “Come, Holy Spirit” hundreds of times throughout the day, in immediate preparation for every situation. If that prayer is good enough for him, it’s good enough for me. While comforting, the Spirit's guidance does not excuse us from all responsibility in developing the coherent response of the Church to the world. St. Peter reminds the faithful that we must "always be ready to give an explanation to anyone who asks you for a reason for your hope" (1 Peter 3:15). Even with the Holy Spirit as our advocate, preparation is necessary. I must be disciplined and conscientious in my study for my upcoming comprehensive examinations. I must continue to grow in prayer, as well as increase my knowledge of my faith and I must be aware of my witness to the faith in word and deed with each person I encounter Yet once the critical moment of speech or witness arrives, just breathe a call to the Holy Spirit and take God’s own Word for it: Do not worry about what you are to say (Lk 12:11). Come, Holy Spirit, fill the hearts of your faithful. Enkindle in us the fire of your love. Send forth your Spirit, and we shall be created, and You shall renew the face of the earth. Laura Berlage holds a M.A. in theology from the University of Notre Dame and currently works as a Pastoral Associate in the Archdiocese of St. Louis, MO. As I settle into my second year at a parish in South Jersey, and find myself responsible for the entirety of programs like First Eucharist preparation and family ministry, I’ve noticed that I must also find my own solution to a continual tension involved in running such programs. I’m calling it “the tension between the urgent and the important.”

There’s a sense of being bogged down by stuff that isn’t important in itself, but is necessary for the important stuff to happen. I don’t want to focus all my sacramental preparation time on ensuring the kids all have baptismal records; I want to make sure we have a coherent plan for how we’re forming them after baptism. I have to be able to find time to look beyond these minor concerns (even if I can’t move on without them) to notice and evaluate where the parish is headed in our ministry, and if that ministry really is allowing Christ to change hearts. Different personalities will use different strategies for managing this tension, so I can’t offer much of an explicit road map. However, we can all agree - it must be managed. If we don’t make time for the visionary in our ministries, we never move forward towards the vision. I understand that this year’s ministry won’t quite comprise the full realization of our eschatological hope, but I’m also in my last year at this parish, and I don’t want to accept continually the deferment, “Next year, we can actually catechize well.” As I contemplated this professional frustration, I realized there was an analogous tension in my life: contemplative prayer. I’ve often heard cited that “finding the time to pray” is difficult, but each of us needs to take a good hard look at what exactly are the things which supercede our prayer lives. As a parish minister, mine are especially ironic - “I can’t pray now, I have to get to work... so that I can balance envisioning the direction of the Church with executing the logistics involved.” I may be well-intentioned, but that prioritization isn’t ultimately fruitful. I cannot say that I am doing the work of the Church, whether important or less important, if I am not also praying through the work of the Church. “Everyone of us needs half an hour of prayer each day," remarked St. Francis de Sales, "except when we are busy—then we need an hour." This pithy quote is a roadmap to balancing the tension between my active ministerial work and the vision, which in this case actually is the Kingdom of God. The Catechism also calls me out: “The choice of the time and duration of the prayer arises from a determined will, revealing the secrets of the heart. One does not undertake contemplative prayer only when one has the time: one makes time for the Lord, with the firm determination not to give up, no matter what trials and dryness one may encounter” (2710). Isn’t it ironic that the trial can be a temptation to plan out the best work of the Church? I have to be able to make (not “find”) time to look beyond my work (even if the Church couldn’t move on without it) to notice and evaluate where I’m headed in my prayer life, and if that prayer life really is allowing Christ to change hearts... especially my own. I don’t want to promise continually, “Tomorrow, I will actually pray well.” Laura Berlage serves as an Echo Faith Formation Apprentice in the Diocese of Camden, NJ One late evening on a camping trip in 3rd grade, my dad and a family friend, Mr. Stroude, took my Girl Scout troop out on a nature walk. We weaved along the path through the woods, giggling with our flashlights dancing around the dirt and moss and trees, until the adults stopped us and asked us to turn off our flashlights. As our eyes adjusted, we realized that we had neared the beginning of a long floating bridge across a large marsh. I say “the beginning” because the length of the crossing and the darkness of the Indiana country meant that, even with my 20/20 vision, I could only see to about the middle of the bridge.

Mr. Stroude proceeded to walk out onto the bridge and soon melted away into the darkness at its center. My dad then explained to us that if we wanted to continue, we would have to walk across the bridge individually, without our flashlight, and meet Mr. Stroude on the other side. “WHAT?!?” More than a little terrifying, Dad! I wasn’t alone in that sentiment. All of us were frightened of the potentially infinite (but definitely creaking) bridge and the murky water beneath it, but no one really wanted to turn back when others might go on without her and see wonderful sights. Eventually, I mustered my courage and stepped out over the marsh into the darkness. I am about to step out onto another bridge, the end of which is covered in darkness. I will soon finish my two years in the Echo program through Notre Dame, and I cannot yet see where God is asking me to go. I cannot see whether I will pass the comprehensive exams for my master’s degree at the end of the summer. I cannot see whether I will have a job come the fall, or even what kind of job may present itself. I cannot see where marriage fits into my future. I cannot see how my relationships will hold up when I move to a new city and leave this community behind. As I pondered all these unknowns, this story from my memory and this prayer from Thomas Merton kept coming forward: My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going. I do not see the road ahead of me. I cannot know for certain where it will end. Nor do I really know myself, and the fact that I think that I am following your will does not mean that I am actually doing so. But I believe that the desire to please you does in fact please you. And I hope I have that desire in all that I am doing. I hope that I will never do anything apart from that desire. And I know that if I do this, you will lead me by the right road though I may know nothing about it. Therefore will I trust you always though I may seem to be lost and in the shadow of death. I will not fear, for you are ever with me, and you will never leave me to face my perils alone. The process of crossing these bridges was and will be a matter of trust. I trusted that my dad would not have asked me to walk a bridge that would not hold me, and I had to recall that trust with each ominous creak. I will trust that Christ is doing the same. I trusted that Mr. Stroude had walked the bridge before me and had already confronted the fears inherent in doing so, and was waiting on the other side, even if I could not see him. I will trust that Christ is doing the same. Of course, I found that each time I reached the darkest part of the bridge, it was no longer completely dark, and there were at least a few more steps to see - enough to allow me to keep walking. I will trust that Christ will show me enough of what’s next to let me keep moving towards Him. Laura Berlage serves as an Echo Faith Formation Apprentice in the Diocese of Camden, NJ... for now. Once, I was a college “mentor-in-faith” for the Notre Dame Vision program, leading small groups for a series of weeklong vocational conferences for high school students. During these conferences, I presented a risky talk[1]. It was risky because I knew there was a possibility of stigma and verbal abuse associated with owning some of my actions. In fact, there was a near certainty of it. However, there was also a real possibility that one or more high school students who had been struggling with sin or guilt could find some real relief, insight, or conversion. When the idea to write this talk first came to me, I found myself unable to brush it aside. Yet I struggled. I went back and forth. Eventually, however, it became apparent to me that there was nothing else to do but to offer this story. So I wrote...

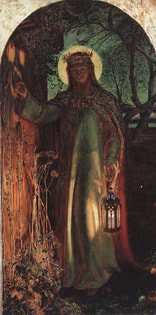

My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord; my spirit rejoices in God my savior. For he has looked upon his handmaid’s lowliness. I closed my talk with these first lines of the Magnificat, as I could understand a little of what Mary was expressing. I was amazed that my soul could proclaim any of the greatness of the Lord to others. My soul? Even in my smallness and brokenness? Yes. Even that brokenness had been turned around to glorify the Lord. Now, compare that simple story to our Mother’s. While Mary had no brokenness, she too had a smallness; an anonymity; even, arguably, a degree of worthlessness to her society. By deciding upon the motherhood of Christ, she accepted the near certainty of stigma, ostracism, even death. Yet through that decision, anonymous young Mary was able to glorify the Lord in an unprecedented way - she is the model of everything the Church can be. She is the model of conforming to God’s will. She is the model of trust in the Lord. She is the model of allowing the Lord to proclaim His greatness through her. In the Magnificat, Mary’s amazement that this could be the outcome is evident (even before she knew it would be). The greatest result was, of course, the Incarnation, and thereby human salvation. I am grateful that she thought the work of God worth the personal risk, both at her first fiat to Gabriel, and at every subsequent time her heart stood in danger of being pierced. I presented a risky talk... once. However, Mary shows us that we are called to take risks for the sake of the Gospel witness more than once in our lives, and without my deliberation born of hesitation. I ask your prayers that both you and I may be given the strength and the spirit to follow Mary’s model, to keep taking the actions that carry with them both personal risk and the corporate reward of building God’s Kingdom. Laura Berlage serves as an Echo Faith Formation Apprentice in the Diocese of Camden, NJ [1] Note: I don’t share that talk’s content here because it involves more than my own story, and the other persons involved have not authorized me to make their story the kind of public that lives online indefinitely. I hope everyone has been enjoying the best season of the year! While secular Christmas music and decor can be nice (and luckily, because they’re ubiquitous), I am referring to the liturgical season of Advent. My friends believe Advent to be my favorite time of year because it typically needs considerable defense against the encroachment of the Christmas season, and I am happy to defend it. We need Advent. In my last post, I stated that if we don’t make time to consider consciously what vision we want to move towards, we’ll never move towards it. Advent is the season during which the Church encourages us to do just that.

So allow me to profess my love for this season. This profession might seem fairly theologically-minded, but I’m a firm believer that thoroughly theological reflection is often eminently practical - when we reflect on our vision, our subsequent actions reflect whether or not we truly envision something important. Looking forward to Christmas alone is the small-minded view of Advent. Yet somehow, it’s the view that even this well-catechized Catholic girl espoused until college – and I don’t think I was alone. Certainly, Christmas is one thing for which we’re preparing. Through our Christmas liturgies, we want to adequately remember and celebrate the miraculous divine self-emptying gift that is the Incarnation, and as always, the salvation that resulted from it. Most Advent calendars and other such aids help us towards this goal. However, when I listen to the Advent liturgies, I hear a different exhortation. The first Sunday alone, we heard of eternal justice, power and great glory, and were told, “Your redemption is at hand.” Even if I listen just to the Lord’s Prayer, the first half expresses our hope for the fulfillment of several things which the original Christmas enabled. These Scriptures point me toward the greater reality for which we are currently preparing: the eschaton, or the reign of God on earth. I’ve always been fascinated by the concept of the eschaton. The Kingdom of God is here already? But not yet? It is “at hand”? What does this language of faith mean? Simple. In one of his homilies on Ezekiel, Pope Gregory the Great compares the joy we have now to the joy in store: “The fire of love which begins to burn here on earth, flares up more fiercely with love of God when he who is loved is seen.” Already, we can welcome the fire of Christ’s love into our hearts. But not yet - that love gets inexpressibly better. Advent is a season of hope, and the true beauty of hope is that we believe one day it will be fulfilled. The greatness of Advent is that eventually it will become obsolete. Take a minute with me this Advent to think about our vision, the Kingdom of God; All injustices will be made right. We will be living with God, in a world without end. We will no longer get in our own way and separate ourselves from Him. We will glorify Him as we should. There will be no holds barred from His all-encompassing love. This is what we wait for. This is our hope. This is the reality of which Advent reminds us, provided we don’t skip past it. How can we be anything but joyful? Laura Berlage serves as an Echo Faith Formation Apprentice in the Diocese of Camden, NJ |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

About |

Media |

© COPYRIGHT 2024 | ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

RSS Feed

RSS Feed