|

“This [the Feast of Pentecost] was to show that just as God in creating man had, as Holy Scripture expresses it, breathed into him the breath of life, so too in communicating a new life to his disciples to live only by grace, he breathed into them his divine Spirit to give them some share in his own divine life. The Spirit of God also ought to come and to rest upon you on this sacred day, to make it possible for you to live and to act only by the Spirit’s action in you. Draw him within you by offering him a well-disposed heart.” — St. John Baptist De LaSalle, Meditation 43.1 Every year at Pentecost, the Church celebrates its birthday, and this year — assuming Christ died in 33 A.D. — the Church will be celebrating its 1,991st birthday. That is 1,991 years of preaching, teaching, and pastoral care for the many and diverse people of God. Each day, I work with ninth and tenth graders in a Catholic high school, teaching them about Sacred Scripture and the Catholic Church. While teaching my sophomores about Church History, I continually receive similar questions: “How did the Church care for its people?” “Why did the Church do that when it seems so wrong by today’s standards?” These questions got me thinking about the Church’s choices in caring for the people of God across history and led me to teach Church history by contextualizing Pastoral Decisions within the historical context of the time period. This led my students to a deeper understanding of the ancient, medieval, and modern ages of the Church. I began this blog post with a quote from St. John Baptist de LaSalle on the gifts of the Holy Spirit given to the Apostles at Pentecost because the same Spirit and gifts have guided the Church since that day. In the early Church, the Holy Spirit guided the Apostles to go out from Jerusalem and preach to the people where they were already living their daily lives. Acts of the Apostles discusses Peter and other Apostles preaching in the Temple in Jerusalem, entering the homes of Gentiles, and traveling to cities across the Roman Empire to speak in public spaces. These first missions sought to bring Jesus’s Gospel message to people in their own cultural context, made possible by the Holy Spirit’s gift of being able to speak various languages from Pentecost. The early Church focused its sacramental life on the “breaking of the bread” or Mass, most likely occurring in people’s homes and dining areas in their preferred language, as seen in the Road to Emmaus story. These personal invitations to the Faith yielded great results and the founding of Christian communities across the Roman Empire. These localized communities, however, soon began to consolidate with new pastoral goals and programs in the aftermath of Constantine’s Edict of Milan which legalized Christian worship, and the subsequent shift of Roman religion from paganism to Catholicism. With Catholicism becoming the state religion of the Roman Empire, the Church gradually became a more established institution. Part of this was the adoption of the use of Latin in public liturgy. Since Catholics could now worship in newly founded Basilicas and Churches, a common liturgical language was needed to cater to all members of Roman society. Additionally, when the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 A.D., effectively breaking up the empire into states ruled by different ethnic groups across Europe, the Church stepped in as a stabilizing institution to help govern and rule a fractured continent. The necessities of common liturgical practices and a united Faith leadership led the Church to influence secular medieval and Renaissance rulers. Many in society today — including my students — look at this era of the Church as the height of Catholic control and corruption, and there were several corrupt leaders within the Church. Nevertheless, when shown as a unifying agent of society — with positive and influential leaders like St. Francis of Assisi, St. Dominic Guzman, and St. Thomas Aquinas — the Church’s evangelization and catechesis efforts come to the forefront. Even today, the Church references the documents and principles of medieval and Renaissance theologians to explain how the Church continues to live its authentic witness to the Gospel in the modern age. The Church of the modern age has naturally progressed from its ancient, medieval, and Renaissance roots. The Holy Spirit continues to guide Pope Francis, the Bishops, and lay leadership across the Church to pastorally respond to the modern needs of the Body of Christ. One of the most notable moments of a pastoral shift in the modern era was the Second Vatican Council, allowing greater expression of cultural diversity in the Church, Liturgy, and personal spirituality. Each Pope since Vatican II has continued to further explain and open the documents of the council for consideration and application among the faithful. In 2019, in his Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation to Young People in the Church, Pope Francis challenges the reader to “above all, in one way or another, fight for the common good, serve the poor, be protagonists of the revolution of charity and service, capable of resisting the pathologies of consumerism and superficial individualism” (Christus Vivit, No. 174). While addressed to young people to be agents of change in society, this is one of many challenges of Pope Francis that beg the faithful to continue witnessing to the Truth of the Gospel and Jesus’s Mission in their own life. Similar messages have been given throughout the long history of the Church, with the only difference being in language and historical context. The singular unifying agent of the Church’s Pastoral Care throughout history has been the Holy Spirit. Today, we must continue to ask the Holy Spirit for help and inspiration in our daily life to help us go forward with the love of Christ to be positive witnesses of the Church today. **This image is from: https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/the-movements-of-pentecost/**

0 Comments

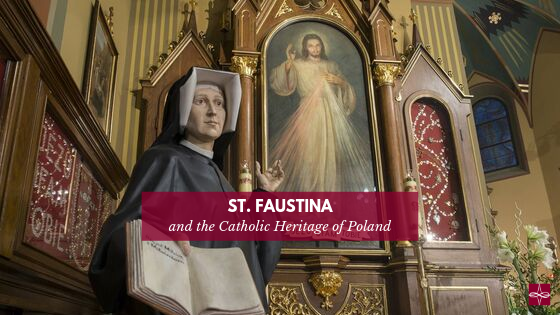

“When I saw the kindness of Jesus, I began to beg His blessing. Immediately Jesus said, For your sake I bless the entire country. And He made a big sign of the cross over our country. Seeing the goodness of God, a great joy filled my soul.” - The Diary of St. Faustina, entry 39 October 5th is the feast day of one of Poland’s great saints: St. Maria Faustina Kowalska. Along with many others, I proudly claim that St. Faustina became my favorite saint after I was introduced to her Diary. Little did I know that this spiritual masterpiece would lead me to fall in love not only with her and the Divine Mercy message, but also with the culture, language, history, and Catholicity of Poland. Since opening Faustina’s Diary for the first time in 2015, I have traveled to Poland twice and learned about other great Polish Catholics such as Blessed Jerzy Popieluszko, Blessed Michal Sopocko, and Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński. I’ve gone deeper into the teachings of Pope St. John Paul II and learned about his own devotion to St. Jadwiga, read about the Polish Solidarity Movement and its leader, Lech Walesa, and much more. I’ve often felt that Poland has its own brand of “Catholic.” There’s the Eastern Rite Catholics, Latin Catholics, and then the Polish Catholics. In the 20th century alone, countless Polish saints have risen from the ashes of two world wars to shine lights of hope, mercy, justice, and love into the world. From its mystics and martyrs to its heroic and internationally beloved pontiff John Paul II, Poland is steeped in Catholicism. You can almost taste it in the air when you hop off the plane at John Paul II Kraków-Balice International Airport or walk the grounds of the Divine Mercy Shrine in Łagiewniki. I strongly hope that future generations treasure Poland’s rich history and the giants that paved the way for them to explore the faith in an incredibly deep and profound way, given the intense historic time periods through which their faith blossomed. Recently, I had a conversation with a friend’s young Polish au pair that made me wonder if this generation does not recognize the gems earned for them by their spiritual ancestors. As I tend to do when meeting anyone from Poland, I rattled off to this young woman about all of my favorite Polish places, saints, and historical moments. She found my love for Poland surprising, and talked about how many young Poles are trying to come to the United States. This puzzled me. Understandably, a country’s own citizens are its biggest critics for a variety of legitimate reasons. But as fellow Catholics, I was hoping for a sense of pride, a recognition of the depth of their history and faith. Maybe, like our country and so many others, appreciation for heritage fades with each passing generation. Indeed, today’s Poles are further removed from the wounds of war and communism than their ancestors, and thus it becomes easy to forget what was fought and won before them. As a result of my time spent in Poland and my subsequent research, I’ve come to admire that it is a place where national culture, identity, and faith was suppressed—unsuccessfully—over and over for centuries. It is a place whose heritage was preserved with blood, zeal, and grit. A place where Catholicism wasn’t freely available but had to be searched for underground and practiced in secret. Poland had to earn where it is today, and past generations understood the price of defending this heritage. Today, when you walk into a church in Poland, you will see a handful of priests hearing confessions before Mass. You will hear beautiful hymns sung—not with heads down buried in the missals, but eyes forward, sung by heart, and with pride. You will hear piercing silence during the consecration of the Sacred Host. You will find standing room only during Mass. You will not be able to find an open store or restaurant two days leading up to Easter. As an American living in a largely secular society, these observations were refreshing to me. Ultimately, Poland’s historical example of turning suffering into mercy, justice, and love has much to teach us not only about the value of a life well lived, but about the value of misfortune well-suffered. From the surrender of St. Faustina, an uneducated peasant turned mystic-nun who penned one of our faith’s greatest spiritual works, to the small, frail priest and martyr Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko boldly, bravely, and publicly proclaiming the truth of Christ directly in the face of communist rule, to the quarry worker and poet-turned Pontiff St. John Paul II, and everyone in between, the saints of Poland show us how we can “shine truth through misfortune,” as Fyodor Dostoevsky once wrote. Every one of the saints mentioned here overcame significant suffering, but through their surrender to Christ, became who they were meant to be, and “set the world on fire.” (St. Catherine of Siena). May you have a happy Feast Day! And if you haven’t, I invite you to open up St. Faustina’s Diary. You’ll be glad you did! Monday, April 15th, was a whirlwind at work. My family alerted me to the fire within the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris. I couldn’t watch the coverage, but the texts continued. The spire fell. The roof caved. My heart sank. I called my sister on my way home and we cried together. It felt so strange, we lamented, to cry for a building. Yet this is not just a building. It is something beautiful, historic, cultural, Catholic, French and so much more. It is transcendent – pointing humanity from something to someone. I stepped foot in Notre Dame in May 2017. I remember the experience like it was yesterday. I have visited many beautiful churches – but Notre Dame was in a category unto itself. Outside, the intricate sculptures and mighty yet delicate buttresses entranced me. Inside, my eyes were drawn higher, higher and higher still. I was overwhelmed – surrounded by the magnificent beauty of stained glass and stone and wood. I thought about the men and women who offered their blood, sweat and tears for two hundred years to build this incredible Church. I sensed that their goal was quite simple: to glorify God. Their work revealed just a small fraction of God’s height, depth, beauty, strength, delicacy, and awe. The Cathedral of Notre Dame is not useful, in the sense that our transportation, jobs, and phones are useful. It is not necessary in the sense that water, food, and shelter are necessary for human survival and flourishing. So why are we weeping at its loss? Because we are made for more than utility and necessity. We are made to glorify God – through who we are, how we live, and even what we create. For centuries, the Notre Dame cathedral has lifted us out of the ordinary into the extraordinary – brought us from the human to the divine – helped us glorify God. While we mourn what has been lost – and rejoice over what has been spared – I believe there is an amazing opportunity before us. In the promised rebuild, we have the opportunity to glorify God anew with the time, talent, and treasure of people worldwide. Six weeks ago, ashes were placed on our foreheads to mark the beginning of Lent. They symbolized a call to refocus on what matters most – our relationship with God. In the days after the fire, we see the ashes from a cherished cathedral. Now, we find ourselves in the midst of the Easter Octave. What is the symbol here? We celebrate Jesus’ death and Resurrection, which offers redemption, restoration and renewal to humanity and to the created world. “See I make all things new” (Rev 21:5). The cross doesn’t have the final say and neither does this fire. The solidarity, generosity and prayers offered from around the world are just the start of God bringing beauty from ashes. For more resources to guide you through the Easter season, please click here. **This post was written prior to the Easter Sunday attack in Sri Lanka. Please join us in prayerful solidarity for our Christian brothers and sisters and all affected by this tragedy. There are about a million things I could say in praise of being a Catholic in Rome. The Eternal City is one of the most significant locations for our faith, and it is almost impossible to come here and not experience Catholicism in some way. Everywhere you turn there is an incredible church that you’ve never even heard of, a monument related to our past, and of course the constant shadow of Saint Peter’s. But beyond that, the history and culture of the city are impossible to separate from the role this place has taken in forming and guiding our Church throughout centuries. You can become almost supersaturated with the beauty of it all, and if you choose it, the experience of being here can be transformative in the faith. But what does it specifically mean to be a young Catholic in Rome? How can you describe the experience of being in one of the oldest places, while simultaneously knowing that you are one of the newest things on the planet? And what responsibilities do we have as young people while here, especially during the current Synod? I am so lucky to be able to study abroad in Rome this semester. One of my classes here is Church History, which includes a weekly visit to a historical site of the faith and a discussion of its role and development within the early Church. I’m a little shocked at how much I thought I knew, and then learning something I never understood about our past. Nothing is more convincing of the fact that the Church is a survivor than one look at its history. The number of upsetting things that I have learned about in the Church’s past are always overcome somehow by the next generation in a manner and consistency that is honestly shocking. Today, this strikes close to home for me, and I’ve come to more deeply see my role and responsibility as a young person called to renew the Church. My course on Church History has been eye-opening in understanding the adaptability and beautifully dynamic nature of our faith, as well as the importance of strong members of the Body of Christ stepping forward to guide her in holiness. In Rome, the city itself is a testimony to the consistency of the faith and its principles, as well as the varied ways this faith has been passed down over the centuries. This is the knowledge that dictates the responsibility of a young person in Rome. It is a gift to be here and a privilege to see these places that hold such significance in our faith. But to view being a young person in Rome as a mere occasion to take and absorb the city without seeing the opportunity and even responsibility to contribute something to the narrative would be a mistake. If there is any place to learn that the Church is built on the living out of the Gospel, it is here, where ancient structures meet the next generation in the ever old-young duality so present in our faith. The Synod of Bishops on Young People, the Faith, and Vocational Discernment is going on in my (current) backyard and is literally designed for me as a young person! One of the coolest sections of the Instrumentum Laboris (the working document of the Synod), in my opinion, is Chapter V, titled “Listening to the Youth,” where it talks about what it means to be open to the real and organic ideas and needs the youth have. It is our responsibility now to take up the Church on her offer to listen to young people by speaking. You don’t need to be the most involved person in the Synod, but perhaps you can learn more about it, read the documents that come forth from this meeting, pray for good fruit to bear, and engage with what is going on. To be in Rome as a young person right now is to be in Rome trying to make our faith more understandable and encounterable for all young people. It is more than an opportunity to evangelize, it is a responsibility. The Synod talks about Jesus’ role as a young man preaching to a young Church. How incredible is it to be the echo of that in the present Church today? May God give us the grace to live that role well. For more resources on the Synod on Young People, the Faith, and Vocational Discernment, please click here. The National Day of Prayer formally began in 1952, but the United States has a history of prayer going back much further. There was much controversy between the founders of our nation about the scale, matter, denomination, and exercise of religion in the public sphere. We do not live in an explicitly Christian nation. Our Founding Fathers were a diverse group of people whose spirituality and religiosity fell on a spectrum ranging from explicitly religious to the more ambiguous. Most were Deist, meaning they believed in a God, but that he was a distant being who did not interact with his creation. Like the idea of the clock-maker, who builds a piece, sets it, and lets it run its own course. As Catholic Christians, we believe in a personal God; a God who wants to be so involved with us and our lives that he became flesh and dwelt among us. But what does that mean for us as American Catholics? I think we are called to be Catholics who live out our faith in the context of an American culture, just as Catholics in France live out their faith in the context of French culture. The virtues our society recognizes, such as care for the poor, can be lived out in a deeply Catholic manner. When we are asked why we care for the poor, our response as Catholics is that humans have an inherent dignity which makes them worthy of care. Our national pride in education and scholarship can be purified with a holistic understanding of the true, good, and beautiful. The love of nature by many in our culture can be viewed as the encounter of the person with the Creator of nature. As Catholics and as citizens, we are called to own our responsibility, our duty of stewardship, to this country in which we live. The concept of stewardship is an ancient tradition in the Church, but is often rarely mentioned beyond the context of tithing and parish finances. The USCCB begins their page on stewardship with this passage from 1 Peter: "As each one has received a gift, use it to serve one another as good stewards of God's varied grace." We as Catholics have been given gifts that other Americans, our fellow citizens, may not have. We have a history and a tradition of prayer, of calling upon God for guidance and protection collectively and personally. We have a community that encourages us to live out the love of Christ for our neighbor. As Catholics, we are called to lead the way in helping those in need, such as young women facing unexpected pregnancies, veterans with mental health issues, and our youth who have a deep longing for the truth in their hearts. Our National Day of Prayer is a day set aside for peoples of all faiths to come together and ask the Almighty for guidance. And our Father is a good Father who cares for his children. It is through his people, the Church, that he acts. As Servant of God Archbishop Fulton Sheen once said, “Show me your hands. Do they have scars from giving? Show me your feet. Are they wounded in service? Show me your heart. Have you left a place for divine love?”I know we live in what feels like a deeply turbulent time in our country and world, but if we let fear rule us then we have no room for love. Is it really the large institutions that determine our national fate, or the many actions or inactions of everyday people in ordinary situations? In The Hobbit, J.R.R. Tolkien had Gandalf remind us, “Some believe it is only great power that can hold evil in check, but that is not what I have found. It is the small everyday deeds of ordinary folk that keep the darkness at bay. Small acts of kindness and love.” Let us go forth in prayer, with Christ in our hearts, and love our neighbors as He taught us. Question for Reflection: How can your faith infuse your daily life and inspire the way you live and act? For more resources on Faithful Citizenship, please click here. For some, Palm Sunday was a political event surrounding a political person that led to the greatest, most unexpected revolution the world has ever seen happen. Historically, the week leading up to Jesus’ Passion would have been the time of preparation for Passover, when many Jews from all the surrounding villages were in Jerusalem together. The gospels (Mt 21: 1-11) describe Jesus’ triumphant entrance into Jerusalem to the swaying of palm fronds and shouts of “Hosanna!” These were unmistakable prophetic signs of the Messiah-king, the one many Jews expected would finally overthrow their Roman overlords and re-establish Israel’s reign on earth, perhaps even violently—as a group called the “Zealots” expected. Yet there is a further symbol to this story: Jesus riding on a colt or ass, the sign of a humble and meek king. Jesus did not become the king they expected, but instead, the one God wanted. As Pope Francis said in his 2016 homily on the Feast of Christ the King, “The Gospel in fact presents the kingship of Jesus as the culmination of his saving work, and it does so in a surprising way. ‘The Christ of God, the Chosen One, the King’ (Lk 23:35,37) appears without power or glory: he is on the cross, where he seems more to be conquered than conqueror.” Like Jesus’ followers then, today we are susceptible to temptations of limited expectations. It is possible to see Jesus merely as a political and ethical teacher who died a martyr’s death and nothing else. On the other hand, we might project Jesus’ kingdom to a purely “other-worldly” realm. Since Jesus apparently wasn’t setting up his kingdom on earth (so we assume), we are tempted to sanitize Jesus of any “worldly” political or practical implications, and simply assume political engagement has limited place, or even runs counter to our task of evangelization. As Pope Pius XI wrote in his establishment of the Feast of Christ the King, “It would be a grave error…to say that Christ has no authority whatever in civil affairs, since, by virtue of the absolute empire over all creatures committed to him by the Father, all things are in his power…although he himself disdained to possess or to care for earthly goods, he did not, nor does he today, interfere with those who possess them.” Both interpretations—that Jesus was strictly political or that his work was merely “not of this world”—fail to take seriously not only Jesus’ public ministry and preaching, but the truly earth-shattering consequences of Jesus’ kingship won at the cross. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that Christ, “exercises his kingship by drawing all men to himself through his death and Resurrection.” Jesus’ death and Resurrection are, simply, God’s victory over the world’s powers of sin and death so as to bring about the restoration of God’s people. To say yes to Jesus’ Resurrection is to say yes to life as part of a new creation and kingdom that starts now. Paschal faith involves the risk of making mistakes, being misunderstood or ridiculed, of not conforming to the expectations of the surrounding culture in order to expect something greater. It involves joining in the kingship of Christ in serving others, something we are able to share in as a result of our baptism. As powers of sin and death today loom heavy on our hearts, it is not enough to “have faith” but to do nothing. Following Christ calls us to witness to our faith in practical ways with full conviction because of Christ’s own experience of suffering, death, and Resurrection that has transformed our fundamental orientation to the world. As Christians, we desire peace, healing, reconciliation, and restoration. We serve our King by building up his kingdom on earth. Pope Francis challenges us, “A people who are holy…who have Jesus as their King, are called to follow his way of tangible love; they are called to ask themselves, each one each day: “What does love ask of me, where is it urging me to go? What answer am I giving Jesus with my life?” For more Lenten and Easter resources, please click here. "When you read God’s Word, you must constantly be saying to yourself, 'It is talking to me, and about me.'"

– Soren Kierkegaard This past fall, while on a retreat, I took a long walk with a friend. As we enjoyed the fresh air, we talked about our spiritual goals and areas for growth. For me, my area for growth seemed clear: I needed to refresh my relationship with the Bible and better use it for meditative purposes. Then my friend, who isn’t Catholic and has what my housemates call “a good Baptist Bible,” said something that made me both chuckle and cringe: “Yeah, I didn’t really know that Catholics don’t really use the Bible too much until I met so many this year.” Cue record-scratch sound. Cue cartoon eyeballs popping out of my head. Cue fumbling words. “Um well, that’s not really true…” I went on to say some jumble of words to correct her and explain the Catholic perspective. The truth is, the Scripture has a deep place in the heart of the Church. As a Catholic, I grew up hearing Old and New Testament alike each week at Mass, and as a (life-long) Catholic school girl, I not only heard and prayed on Bible stories but studied them. I am very grateful for my education; even if I can’t quote chapter and verse, I have a good understanding of the Bible’s history & context, as well as its eternal Truths. Yet clearly, my failure to embrace Scripture as a meditative and prayerful tool more closely looked to some (particularly non-Catholic Christians) as a general ignorance or dismissal of it. One thing you learn quickly in Bible-belt Kentucky is that people love and KNOW their Bibles. My friend’s comment made it clear: The Bible is important, and I needed to get my stuff together and meet God’s word more personally. So I did. I started a plan to read a little of the Old Testament, the Psalms, and the New Testament each day. Two months into this plan, I realize that while it is the story of God’s revelation to us, God’s people, it is also a revelation of myself, of who I am in relation to God. While for many, the Bible brings them close to know God, I find that reading it makes me stop and go, “Just who are you, God?! And how are you calling me?” (I imagine God hears this and chuckles, thinking It’s working!) But as a housemate reminded me, the Bible wasn’t made to be an easy read. I won’t ever “finish” it and be done, and God won’t give me a “Good Christian Award” just for reading it cover to cover. Though I already knew many of these stories and words well, they feel new to me. When I read it with a prayerful mind, and not an analytic, academic one, I see myself in the stories: my own failings, my own desires, my own questions. I won’t be able to quote chapter and verse at the end of this year; nor will I have a “good Baptist Bible” covered in ink and Post-It notes. But I’m learning to approach Scripture less like Martha (“Did I do it right? Am I on schedule?”) and more like Mary, simply by being with it. Then again, ask me how I feel in a few weeks when I get to Deuteronomy and Leviticus. Katherine Biegner recently graduated from Assumption College and is currently serving as a tutor and mentor in the Christian Appalachian Project in rural Kentucky. Without a doubt, the Gospel of John is my favorite book in the Bible. I love the mixture of philosophy and poetry in Jesus’ monologues. It is beautiful how it captures the whole of Salvation History. And it seems that it has quite possibly some of most quotable and recognizable verses in all of Scripture such as Jn. 3:16. Yet the simplest reason is that it contains the profound dialogue that Jesus and St. Peter have post-Resurrection in the 21st chapter.

The scene is simple: Jesus and Peter are sharing a meal on the shore of the Sea of Galilee. Jesus asks a seemingly simple question especially for a man who is supposed to be the “rock” (Mt. 16:18) of the Church- “Do you love me?” Peter affirms his love for Jesus and then Jesus proclaims, “feed my sheep”. This sequence happens two more times, which shows Jesus’ mercy and sense of humor. As you probably know, Peter denied Jesus three times rather than stand up for his faith and Savior. This is Jesus allowing Peter to make up for his threefold denial with a threefold affirmation. Unfortunately, the English translation does not fully capture the drama of this story and thus, we must look to the original Greek. The Greeks had three words for our word, “Love”: Philia (Friendship), Eros (Sexual Love), and Agape (Selfless, Gift-Love). In the context of this story, Jesus asks Peter, “Do you Agape me?” In his shame, Peter can only respond, “I Philia you” or “I am your friend.” While Jesus loves Peter with his whole heart, Peter is a wounded human. On the third try, Jesus meets Peter at his level and asks if they are friends. To this, Peter can agree. From November 5 to 17, 2012, I had the tremendous opportunity to be part of a pilgrimage to the Middle East. What made the trip special was that I got to spend the time with my mom, who has been a great role model and exemplar of sacrifice and faith. And while seeing the Pyramids in Egypt and Petra in Jordan were great, the part that I was most excited for was the Holy Land. One of the places that we went to was the Church of the Primacy of St. Peter, where it is said that Jesus and St. Peter had this final conversation as told in Jn. 21. Like many of the other churches that we went to in Israel, I automatically felt the sacred presence of the Spirit. I went into the Church first to say a prayer and then walked along the shore of the Sea. I was so utterly moved to be standing on the ground and touching the water where Jesus and Peter shared this intimate moment. I was speechless to be present there and just gave thanks for this blessing. The words that I kept praying were the words of Jesus’ command to Peter: Feed my sheep. All my life, I viewed my Catholic faith as an opportunity to be a role model for others. I participated in parish ministry through the Echo Program and taught high school Religion for two years. Now, I am taking a year off to discern my next step in my life journey and where exactly God is calling me to serve his people, to “feed [his] sheep”. Wherever I end up, I will be grateful and remember the incredible time that I spent on the shore of Galilee. The place that Jesus asked Peter a simple question for all of humanity, “Do you love me?” Tae Kang has his MA in Theology from The University of Notre Dame through the Echo Faith Formation Program and has worked both as a Lay Ecclesial Minister in a Parish and as a High School Religion Teacher. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

About |

Media |

© COPYRIGHT 2024 | ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

RSS Feed

RSS Feed