|

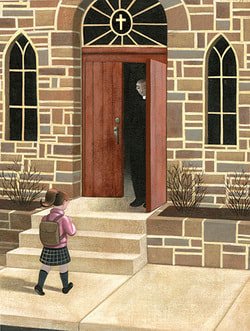

“This [the Feast of Pentecost] was to show that just as God in creating man had, as Holy Scripture expresses it, breathed into him the breath of life, so too in communicating a new life to his disciples to live only by grace, he breathed into them his divine Spirit to give them some share in his own divine life. The Spirit of God also ought to come and to rest upon you on this sacred day, to make it possible for you to live and to act only by the Spirit’s action in you. Draw him within you by offering him a well-disposed heart.” — St. John Baptist De LaSalle, Meditation 43.1 Every year at Pentecost, the Church celebrates its birthday, and this year — assuming Christ died in 33 A.D. — the Church will be celebrating its 1,991st birthday. That is 1,991 years of preaching, teaching, and pastoral care for the many and diverse people of God. Each day, I work with ninth and tenth graders in a Catholic high school, teaching them about Sacred Scripture and the Catholic Church. While teaching my sophomores about Church History, I continually receive similar questions: “How did the Church care for its people?” “Why did the Church do that when it seems so wrong by today’s standards?” These questions got me thinking about the Church’s choices in caring for the people of God across history and led me to teach Church history by contextualizing Pastoral Decisions within the historical context of the time period. This led my students to a deeper understanding of the ancient, medieval, and modern ages of the Church. I began this blog post with a quote from St. John Baptist de LaSalle on the gifts of the Holy Spirit given to the Apostles at Pentecost because the same Spirit and gifts have guided the Church since that day. In the early Church, the Holy Spirit guided the Apostles to go out from Jerusalem and preach to the people where they were already living their daily lives. Acts of the Apostles discusses Peter and other Apostles preaching in the Temple in Jerusalem, entering the homes of Gentiles, and traveling to cities across the Roman Empire to speak in public spaces. These first missions sought to bring Jesus’s Gospel message to people in their own cultural context, made possible by the Holy Spirit’s gift of being able to speak various languages from Pentecost. The early Church focused its sacramental life on the “breaking of the bread” or Mass, most likely occurring in people’s homes and dining areas in their preferred language, as seen in the Road to Emmaus story. These personal invitations to the Faith yielded great results and the founding of Christian communities across the Roman Empire. These localized communities, however, soon began to consolidate with new pastoral goals and programs in the aftermath of Constantine’s Edict of Milan which legalized Christian worship, and the subsequent shift of Roman religion from paganism to Catholicism. With Catholicism becoming the state religion of the Roman Empire, the Church gradually became a more established institution. Part of this was the adoption of the use of Latin in public liturgy. Since Catholics could now worship in newly founded Basilicas and Churches, a common liturgical language was needed to cater to all members of Roman society. Additionally, when the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 A.D., effectively breaking up the empire into states ruled by different ethnic groups across Europe, the Church stepped in as a stabilizing institution to help govern and rule a fractured continent. The necessities of common liturgical practices and a united Faith leadership led the Church to influence secular medieval and Renaissance rulers. Many in society today — including my students — look at this era of the Church as the height of Catholic control and corruption, and there were several corrupt leaders within the Church. Nevertheless, when shown as a unifying agent of society — with positive and influential leaders like St. Francis of Assisi, St. Dominic Guzman, and St. Thomas Aquinas — the Church’s evangelization and catechesis efforts come to the forefront. Even today, the Church references the documents and principles of medieval and Renaissance theologians to explain how the Church continues to live its authentic witness to the Gospel in the modern age. The Church of the modern age has naturally progressed from its ancient, medieval, and Renaissance roots. The Holy Spirit continues to guide Pope Francis, the Bishops, and lay leadership across the Church to pastorally respond to the modern needs of the Body of Christ. One of the most notable moments of a pastoral shift in the modern era was the Second Vatican Council, allowing greater expression of cultural diversity in the Church, Liturgy, and personal spirituality. Each Pope since Vatican II has continued to further explain and open the documents of the council for consideration and application among the faithful. In 2019, in his Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation to Young People in the Church, Pope Francis challenges the reader to “above all, in one way or another, fight for the common good, serve the poor, be protagonists of the revolution of charity and service, capable of resisting the pathologies of consumerism and superficial individualism” (Christus Vivit, No. 174). While addressed to young people to be agents of change in society, this is one of many challenges of Pope Francis that beg the faithful to continue witnessing to the Truth of the Gospel and Jesus’s Mission in their own life. Similar messages have been given throughout the long history of the Church, with the only difference being in language and historical context. The singular unifying agent of the Church’s Pastoral Care throughout history has been the Holy Spirit. Today, we must continue to ask the Holy Spirit for help and inspiration in our daily life to help us go forward with the love of Christ to be positive witnesses of the Church today. **This image is from: https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/the-movements-of-pentecost/**

0 Comments

"Since you are ambassadors and ministers of Jesus Christ in the work that you do, you must act as representing Jesus Christ himself. He wants your disciples to see him in you and receive your instructions as if he were giving them to them. They must be convinced that your instructions are the truth of Jesus Christ who speaks with your mouth, that it is only in his name that you teach, and that it is he who has given you authority over them.”—St. John Baptist de la Salle The entirety of the baptized are, as St. Paul says, “ambassadors for Christ,” but St. John Baptist de la Salle—the patron saint of teachers—expands on this idea for educators of the youth. La Salle sees teachers as becoming the image of Christ for students in the classroom. This idea necessitates that teachers teach their disciplines well, but they must also be models of love and virtue for their students. As a Secondary Education and History student observing at a Washington D.C. Catholic middle school, I have recently reflected on my role as a classroom teacher. Teachers, in many ways, become an extension of the domestic church. As children reach kindergarten age, they begin to spend the vast majority of their weeks—close to seven hours a day Monday to Friday—in the care of their teachers. The sheer amount of time students spend with their teachers necessitates that teachers become another guardian for their students. I have seen this first-hand in an eighth-grade class I have been observing. Students look to their teacher for guidance and reassurance, and their teacher provides structure, help, and correction for each student as needed. Particularly, in middle and high school, teachers begin to form students’ adolescent and adult mannerisms, and a teacher’s embodiment of Christ’s charity is essential for students to see how the Christian life is lived. Students crave a person to model, and while Jesus is the perfect example, it is hard for many to conceptualize how Jesus lived as a human being. La Salle explains, “Example makes a much greater impression on the mind and the heart than words, especially for children, for they do not yet have a mind sufficiently able to reflect, and they ordinarily model themselves on the example of their teachers” (la Salle, Meditations for Time of Retreat). A teacher must then step in as a witness to Christ’s mission lived out in the modern world. Teachers cannot be aloof people who look perfect to students. Instead, instructors must show that they are human with the capacity to make mistakes in classroom instruction and in working with their students. Over this semester of observations, I have noticed that students will eventually place their trust in you as they get to know you. As I assisted students with their classwork, asked them questions about their class and school, and talked about life, they slowly began asking me questions and fostering conversations with me. This culminated when I taught a complete lesson on the Roaring 20s and the Harlem Renaissance. My students engaged with me throughout the class period, and they even offered me feedback like a need to slow down a little and explain my slide images more. Students were also appreciative that I did not have all the answers to their questions, but I followed them up by saying, “let me check on that and get back to you.” Teachers must show students that they are an authority on their content and should be a trusted source of knowledge, but they also have limitations and do not know every single fact on a subject. Teachers—like pastoral ministers—must recognize the gravity of their role and hold themselves to a high moral and professional standard, but they must also be down-to-earth and relatable. This relatability in the classroom for middle and high school students allows for a form of collaboration where teachers and students work together to pursue the truth and the Christian life. St. John Baptist de la Salle was constantly trying to teach his order of teaching brothers that they were ministers of the Church and Christ and that the salvation of students lay within their hands as teachers. La Salle asked teachers to give of themselves to inspire their students in their academics and faith lives because he realized that students craved authentic witnesses to the theological and human truths of life. St. la Salle explained himself best when he wrote, “for the love of God ought to impel you, because Jesus Christ died for all, so that those who live might live no longer for themselves but for him who died for them. This is what your zeal must inspire in your disciples, as if God were appealing through you, because you are ambassadors for Jesus Christ” (la Salle, Meditations for Time of Retreat). In many ways, St. la Salle preempted modern evangelization practices with his emphasis on authentic witness as a means to bring people closer to God. To learn more about the saints, visit our Catholic Feast Days Website by clicking here.

If you attended an Easter Vigil Mass this year, then you participated in what St. Augustine called the “mother of all holy Vigils”(Sermo 219)—the day the Church receives many new Catholics through the sacraments of initiation: Baptism, Eucharist, and Confirmation. The newly baptized, or “neophytes,” (a Greek word meaning “new plant”) begin a fourth and final period of formation called mystagogy, which lasts the Easter Season until Pentecost. If you haven’t personally participated in the formal process of becoming Catholic as an adult (called the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults, or RCIA, in parishes), chances are you haven’t heard this word recently… or maybe ever. What is Mystagogy? Our faith needs mystagogy first and foremost because of one simple reason: we celebrate and proclaim a mystery. As evangelists and catechists, I think it is important to recognize that for some people, the idea of religious “mystery” prima facie, conjures up images of a Da Vinci Code-esque Church shrouded in secrecy, New Age spiritualism, or even a pre-scientific belief in “magic.” But the sacraments do not initiate us into a special club or secret society. Through them, we are made participants in the life of Jesus Christ. Faith begins and ends in mystery, most especially the mystery of the Most Holy Trinity, “the central mystery of Christian faith and life . . . the source of all other mysteries of faith” (CCC 234). In the scriptures, liturgy, and sacraments, we truly encounter and participate in the Triune life of God. But no matter how intelligent or insightful we are, we will never fully wrap our minds around God’s glory or totally experience it with our five senses. Mystagogy comes from the Greek word meaning, “to lead through the mysteries.” The Catechism describes mystagogy as a “liturgical catechesis that aims to initiate people into the mystery of Christ” (CCC 1075). Mystagogy leads us from the external signs and rituals of the liturgy to the inner, spiritual meaning of the divine life they signify. Mystagogy is the form of catechesis that helps us unpack and explore the spiritual treasures contained in the sacraments by continuously reflecting on their meaning and significance in our personal lives of faith. Mystagogy was the way the early Church Fathers embraced and trained new Christians in the practices and beliefs of the faith. Perhaps the most well known teacher of mystagogy was St. Cyril of Jerusalem (315-386 CE), who delivered a famous series of sermons, known as “mystagogic catecheses,” during the time of Lent through the Easter Octave. After the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic Church revitalized this ancient practice, especially in the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults. But mystagogy isn’t just for the newly baptized; it is the way every Catholic can continually deepen their relationship with Christ by daily drawing on the grace of the sacraments. Significance for our New Evangelization Just as Catholics are rediscovering the importance of the “kerygma” (Greek for “proclamation”) for evangelization, mystagogy is incredibly important in our approach to catechesis in the New Evangelization. John Paul II wrote, “Through catechesis the Gospel kerygma is gradually deepened . . . . and channeled toward Christian practice in the Church and the world” (Catechesi Tradendae, n. 25), specifically the form of mystagogy. Additionally, mystagogy serves as a trustworthy guide when reflecting on ways to improve our catechetical methods. Living the Mystery Daily Ongoing mystagogy is important because our relationship with the sacraments change as we grow and mature as individuals and meet new life challenges and circumstances. In turn, the sacraments really change us. Pope Benedict XVI said, “The mature fruit of mystagogy is an awareness that one's life is being progressively transformed by the holy mysteries being celebrated” (Sacramentum Caritatis n. 64). By reflecting regularly on the sacraments, we access an incredible strength for our daily tasks. Developing a practice of Eucharistic mystagogy can combat the routinization that often sets in to our receiving communion. For those who are married, or preparing for marriage, there is a mystagogy of marriage. With ongoing mystagogic reflection, you may discover new fruits of that sacrament in every season of life. Studying theology and the Bible is often an undervalued way of developing our spiritual life. Learning about someone or something is a sign of love, and we truly become what we behold (cf 2 Cor. 3:18). Reading the great books and sermons of Catholic authors and theologians greatly expands our hearts and minds to experience the truth and depth of our faith. The great Catholic philosopher Gabriel Marcel is attributed as stating, “Life is not a problem to be solved, but a mystery to be lived.” Mystagogy is the path leading Christians to learn to live the mystery of our faith. I encourage you to follow the path trod by St. Cyril up through popes John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis, in making this incredible tradition and gift called “mystagogy” a part of your life. To learn more about Catechesis, please consider reading the General Directory for Catechesis or the National Directory for Catechesis. For more resources on Prayer and Catechesis, click here. “Let us remember that we are in the holy presence of God.” With these words, I and students of Lasallian schools around the world would pause before class to contemplate and center ourselves on this truth. This call to prayer tended to have the effect of stilling the room, if only for a few moments of silence, but I especially appreciated turning my focus to God before carrying on with my day. Even after I graduated from high school, I was able to cherish this simple ritual even more as I would go through my busy routine at The Catholic University of America. I found that even the simplest acknowledgement of God— this small act of love— would help me endure the challenges of the day. The Church celebrates the feast day of St. John Baptist de La Salle on April 7, though his institutions continue to celebrate on May 15, the date of his original feast day until 1969. Students of De La Salle’s schools may be very familiar with his biography, whose life’s works are the very foundation of their education. De La Salle was born to a wealthy family in Reims, France in 1651. At that time, most children had little hope for social or economic advancement. Seeing how the educators in his hometown were struggling, lacking leadership, purpose, and training, De La Salle determined to put his own talents and education at the service of the children “often left to themselves and badly brought up.” Having donated his inheritance to the poor of the famine-afflicted province of Champagne, De La Salle began a new religious institute, a community of consecrated laymen to run free schools “together and by association,” the first with no priests among its members: the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, known in the United States as the Christian Brothers. His community would grow to succeed in creating a network of quality schools throughout France that boasted revolutionary educational practices such as instructing in the vernacular, grouping students according to ability and achievement, integrating religious and secular subjects, having well-prepared teachers with a sense of vocation and mission, and involving parents. Today, the Christian Brothers are assisted by more than 73,000 lay colleagues, teaching over 900,000 students in 80 countries. As a “Brother’s boy,” each of my peers and I would learn to take up our studies as well as our friendships with gusto and dedication, being made ever aware of the gifts God had given each of us. The life of De La Salle was especially studied as part of the freshmen curriculum, but each student was expected to emulate his example of charity and spirituality through and beyond graduation. St. John Baptist de La Salle showed others how to teach and care for young people, how to meet failure and frailty with compassion, and how to affirm, strengthen, and heal. His advice to his community of educators still rings true for the countless students taught in his name: “to do all [your] actions for the Love of [God] … with all the affection of your heart” and to “hold prayer in high esteem as the foundation of all the virtues, and the source of all grace needed to sanctify [yourselves].” The Brothers I was blessed to have as mentors surely strove to follow this example in all aspects of their lives; they’d encourage us to simply be aware of and open to God’s will. Returning to prayer, then, was essential to the ministry of St. John Baptist de La Salle. I would and still marvel over how truly beautiful is the sight of seeing students pray before class, meals, games, and trips —not just out of need or a particular want, but out of love, faithful devotion, praise, and thanksgiving. Especially in times of global, local, or personal strife, the small chapel in the corner of my high school would always contain at least one of my peers before the Blessed Sacrament. Of the many gifts our beloved founder gave to the modern education system, I especially cherish the routine of prayer instilled in my life and that of countless others. Not only would we remember our being in God’s holy presence, but also that God Himself faithfully, lovingly, eternally, and supportively lives in each of us. “Saint John Baptist de La Salle, pray for us!” “Live, Jesus, in our hearts! Forever!” For more resources on Prayer and Catechesis, click here. “The work of teaching is one of the most important in the Church.”

~St. John Baptist De La Salle Today, we often take for granted Catholic schools. Most likely either you or someone you know attended a Catholic school. A Catholic education is often seen as top quality, and Catholic schools are considered some of our finest places of learning. The modern concept of education dates back to the late 17th century France and one individual in particular: St. Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, founder of the Brothers of the Christian Schools. His work was not only revolutionary in method, but also unique in terms of educating the poor and underprivileged. Some 300 years later, de La Salle’s vision of educating those most in need remains strong in the United States through the Miguel model school. The Miguel school system was established in 1993 with the sole purpose of educating under-served children, focusing on students in middle school. The system was named after St. Miguel Cordero, a Christian Brother who dedicated his life to the education of poor Ecuadorians. Recent news about families and children fleeing their homes in Central and South American to find better educational and economic opportunities demonstrates that the need for quality education is as great today as in the time of St. Miguel. Here in Washington D.C., a Miguel school was established in 2002 as an extension of St. John’s College High School with 8 students – San Miguel School of Washington. It rapidly grew, and this past year the school graduated its largest class of 23 students and currently has a total of sixty-three Latino boys in grades six to eight. All San Miguel students come into sixth-grade from DC public schools and, on average, have reading and math skills of a fourth-grader. By the end of their time at San Miguel as eighth graders, they are 100% proficient in these subjects. [1] This success results from their own hard work and that of experienced teachers and tutors. Additionally, San Miguel, like most Miguel-style schools, operates on an extended day and year-round school program (200 school days vs. a traditional 160 days). This hard work pays off - 98% of San Miguel graduates have either completed their high school diploma or are in the process of doing so. The graduation rate for Latino males in DC public schools is 46% [2]. Clearly, San Miguel and its unique style of education is paying off. In addition to my role at the Catholic Apostolate Center, I work as an intern in the Development Office at San Miguel School. It has been an exciting time and a true blessing to work to make sure that San Miguel students receive the education they deserve. It has helped me to grow in trust for the good work that the Church does as a whole. We as Catholics have the obligation to serve others, as apostles of Christ. We have the responsibility to do our part in the greater effort of Christ’s mission. San Miguel School truly changes the lives of its students. By serving these at risk Latino boys, I know that I am changing the world and trying to do my part. Patrick Fricchione is the Research and Production Associate for the Catholic Apostolate Center and an intern in the Development Office of San Miguel School. [1] San Miguel School DC, website, sanmigueldc.org. [2] Statistic from the National Center of Education Statistics. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

About |

Media |

© COPYRIGHT 2024 | ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

RSS Feed

RSS Feed