|

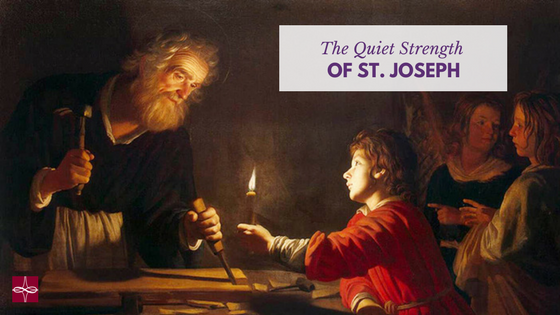

This weekend is the feast of St. Patrick—one of the most popular saints in the Archdiocese of Washington where I grew up and arguably in the entire United States. But two days later on March 19, coming much more quietly and with far less fanfare in American culture, slips in the Solemnity of St. Joseph.

It is easy to lose the Solemnity of St. Joseph in the rigors of Lenten observances or because it comes on the heels of the day-long party that seems to happen every year on St. Patrick’s Day. Perhaps we often overlook this feast because we know so little about who St. Joseph was and what his life was like. Nevertheless, St. Joseph remains an incredibly important figure, especially for parents. Joseph is mentioned only a few times in the New Testament. We know from the Gospels that Joseph was a law-abiding and righteous man, and that he obeyed God’s will—especially when it was revealed to him directly by an angel. After these few mentions in the infancy narratives of Jesus, St. Joseph gently fades into the background and then disappears altogether from the Gospels. But the Church in her wisdom has made St. Joseph’s importance clear for those who are paying attention: he is mentioned in all four Eucharistic Prayers at Mass, as well as in the Divine Praises during Benediction at the end of Eucharistic adoration. But what makes St. Joseph so special? From what we can glean from the Gospels, St. Joseph was an ordinary man of deep faith who was called to become the foster-father of Christ. He became the earthly guardian of the Messiah, responsible for his upbringing and tasked with protecting him in his early life. St. Joseph’s commitment to his vocation as the husband of Mary and the foster father of Christ was so strong that upon being warned about the murderous intentions of King Herod, he fled immediately—in the middle of the night!—to Egypt. He did whatever it took, even leaving his entire life behind him, in order to keep his family safe. The little we see of him in the New Testament shows us a devout man who always trusted in God and took care of his family. St. Joseph, as the third member of the Holy Family, is the member who is the most like us—especially those of us who are parents. He was not born sinless, nor was he divine. He was a carpenter, a man of humble station who probably felt as though he had a monumentally important task thrust upon him. I think St. Joseph’s role in Christ’s life beautifully displays the role of a Christian parent in their child’s life. Parents are ordinary people who are tasked with the care and raising of new life. Like Joseph, we do not own our children or have sole claim over them; they are their own people, entrusted to our care and guidance until they grow old enough to do God’s will without our assistance. It is a difficult task, and at times overwhelming to ponder. And yet there is St. Joseph, who was tasked with raising the very Son of God. Joseph shows us that we do not need to be perfect in our roles, only willing to be guided by God as we place our trust in Him. Just as I strive to be like Mary in my vocation as a wife and mother, I pray that my husband will be like Joseph. St. Joseph is the ultimate husband and father, a faithful man of quiet strength, protector of Mary’s virginity, and guide of Christ’s earthly childhood. Above all, St. Joseph shows us the beauty of a life lived in obedience to God’s will. Questions for Reflection: How can you grow closer to St. Joseph throughout this Lenten season? What can you learn from St. Joseph’s example of obedience and trust?

0 Comments

I have been taught lectio divina in the past, which I practiced fervently at one time and set aside as I pursued other spiritual interests. Lectio divina, though, has never been put together for me quite the way Fr. Chris Hayden (a New Testament scholar, author, and a priest in the Diocese of Ferns, Ireland) was able to do when I recently attended his seminar “Praying the Scriptures.” As a result, I have refreshed my own spiritual life and have reincorporated lectio divina into my spiritual repertoire. My point here is not to relay new facts but (as Fr. Chris would say) to rehearse what we already know – to cement who we are as a people who want to pray, who want to grow in the spiritual life.

Lectio divina (Latin for “divine reading”) was not something new to Christians but flowed out of the Hebrew method of studying the Scriptures, haggadah, or learning by the heart: “The word is very near to you; it is in your mouth and in your heart for you to observe” (Deut 30:14). While many Church Fathers stressed the prayerful reading of the scriptures, Origen is credited with the first use of the term “lectio divina” in the 3rd century: “While you attend to this lectio divina, seek aright and with unwavering faith in God the hidden sense which is present in most passages of the divine Scriptures” (Epistle to Gregory 4). Traditionally, lectio divina is a Benedictine practice of praying the scriptures that consists of reading, meditating, praying, and contemplating God’s Word in order to grow in our relationship with God. Saint Benedict first established it as a Monastic practice in the 6thcentury in which the four parts were not so much steps but rather moments prompted by the Holy Spirit. During the 12th century, the Carthusians formalized a scholastic approach (“the Monk’s Ladder”) of lectio (reading), meditatio (meditation/reflecting), oratio(prayer/responding), and contemplatio (contemplation/resting). We distinguish lectio divina from reading the Bible for enlightenment or encouragement, which we may do individually or together as in a Bible study group, and from praying the scriptures in common. Lectio divina is a practice that uses thoughts, images, insights, and inner silence to enter into a conversation with God. There are varying approaches to lectio divina, but in reality, simplicity is at the heart of the practice. After Vatican II and the document Dei Verbum that encouraged lay people and priests to use lectio divina, there has been a resurgence in its exercise. When we read Scripture, we should be doing so not just as an intellectual activity but also as a means of gathering its intention and meaning for our lives. Lectio divina will transform you for transformation is at its core – whether you realize that transformation consciously or not, and whether you reflect that transformation visibly or not. To appreciate fully lectio divina, we must understand prayer as a relationship between God and ourselves. Through prayer, we enter into the abiding relationship of unconditional love of the Holy Trinity. Three key underpinnings of our prayer life should be humility, heart, and listening. In prayer, we enter into humility, deflating our egos, realizing we are not God. Our humility helps us discern the true self from the false self. We continue to pray in order to break open our hearts to God, to realize what is going on inside ourselves for the heart of prayer is not what we get but rather what we become. We all know we should be receptive to God heeding the advice of Eli to Samuel, “Speak Lord, your servant is listening” (1 Sam 3:1-10), but many of us might prefer to tell God in prayer, “Listen Lord, your servant is speaking!” As anyone who has been successful with Christian meditation or contemplative prayer will attest, we need to make time and spaces for silence so we can listen. What should we do, though, if our prayers seem to be unanswered? Fr. Chris offers five guides or reasons to continue in prayer (he admits, certainly, there is not just five, but I find the five he presented crucial) even when our prayer life seems to be in a drought:

Because we have the Bible, the living Word of God, our spirituality is not a set of speculations. The Bible is our story – our metanarrative. Our metanarrative unites all of our individual stories into a collective under the overarching theme of God’s eternal love. We find today that the separate designations of yours and mine drive our society; today’s society is certainly no metanarrative, no uniting of us all. Within the Biblical texts, however, we find our collective and individual stories in which we participate along with Christ in the Trinitarian love. We can break our metanarrative into four acts: Act I: The beginning; Act II: The Fall; Act III: Redemption; and Act IV: Fulfillment. Our story begins with life (the “Tree of Life” in Genesis) and ends with life (the “New Order” in Revelations as found in Christ.) We find ourselves living in the drama between Acts II and III, that constant struggle of our lives that tugs between our disobedience and our obedience as we reach for that time of fulfillment. With this acceptance of the Bible as our metanarrative and our understanding of prayer, especially the reasons for continuing in prayer when our prayer life is dry, we can appreciate the power of praying the scriptures to transform our lives. Lectio divinabecomes, in reality, so simple.

Fr. Chris told me not to give him credit, but I must at least thank him for traveling to Great Falls, Montana, for sharing his joy of the faith, and for his stimulating way of presenting prayer, scripture, and the ancient art of lectio divina that inspired me to take a fresh look at how I pray the scriptures. I hope I have given him due credit by relaying the simplicity of lectio divina and its importance in helping us live out our shared metanarrative of God’s love. With Fr. Chris’ inspiration, I renew myself to the simplicity of lectio divina, enhancing my spiritual life, and I pray: God help us live our story, our metanarrative, as we pray for our transformation in You, our destination. Fawn Waranauskas teaches in the Catholic Catechesis Certificate Program for Saint Joseph’s College Online. This blog post was first published on May 27th on the St. Joseph’s College of Maine Theology Faculty Blog. Click here to learn more about our cooperative alliance with St. Joseph’s College Online  “Faith Seeking Understanding” is the motto of St. Anselm of Canterbury, whose feast we celebrate today, is a reminder to all Christians to seek God not only with our hearts but with our minds as well. St. Anselm, a Benedictine monk who lived during the 11th century, was known throughout Europe for his mind. He was a great scholar and strategist, having often put his wits against those of the English monarchy to try and preserve his own life and the life of the Church in England. However, his exercise of intellect during his life is not the “understanding” that his motto would prompt us to seek, nor that which lead him to be canonized a Saint. Rather it is the knowledge which Pope Francis spoke of in his general audience on May 21, 2014 “When we speak of knowledge, we immediately think of man’s capacity to learn more and more about the reality that surrounds him and to discover the laws that regulate nature and the universe. The knowledge that comes from the Holy Spirit, however, is not limited to human knowledge; it is a special gift, which leads us to grasp, through creation, the greatness and love of God…” This kind of knowledge, the knowledge of God, is far more precious than any other. How then do we obtain this most precious knowledge? St. Anselm would probably quote the words the founder of his order, St. Benedict, by saying “ora et labora” (pray and work). Indeed prayer and work, focused on God, will help lead someone to better understand God. Pope Francis, in that same audience on May 21st, gives us a possible focus for that prayer and work: creation. The Holy Father noted that although God gave the gift of His creation to man, that does not make mankind the “masters of creation.” The Holy Father continued by saying that “creation is not some possession that we can lord over for our own pleasure; nor, even less, is it the property of only some people, the few: creation is a gift…” All around us, especially as new life comes forth during this spring season, we can see God’s creation in its majesty. We must work then to care for it but also reflect and pray upon it. We must always seek to understand God so as to better conform our own lives to His will. Faith is a gift, and having faith is not the end of a journey but the start of a new one. St. Anselm teaches us that we must use our faith to seek understanding of the world around us and of the God who created us! Patrick Burke is a staff member at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.

Just last summer on Copacabana Beach, at World Youth Day, Pope Francis remarked, “The Church is counting on you... The Pope is counting on you!” Youth in the Church today often feel marginalized, alone, or worst of all- downright ignored. However, it is our calling as baptized Catholics to reverse this trend, and in rural southern Indiana, an unlikely group of Catholics are striving to do just that.

I spent the summer at Saint Meinrad Archabbey, a Benedictine monastery in Indiana, working for One Bread One Cup, a liturgical leadership youth program that forms high school students in the liturgy and helps them to integrate the Word, Sacrament, and Mission of the Church into their lives. Over seventy monks welcomed twenty college interns and hundreds of high school students and youth ministers to their home. However, they did much more than welcome us to their home. For centuries, Benedictine monks have been known in a special way as guardians of the rich liturgical patrimony of the Church. And guess what they did with it? They gave it away, they gave the youth the most precious gift that they have, telling them to go back to their parishes and implement what they have been taught, ranging from how to be an EMHC, to Cantor, to liturgical artist. However, it was not so much being taught how to do these things, as much as helping the youth to realize and use their God given gifts to build up His Kingdom. Whenever I think of the mission of One Bread, One Cup, I always see its mission epitomized by Matthew, Chapter Ten, when Jesus commissions and sends out the apostles to minister, to go and proclaim the kingdom of heaven. An important aspect of the New Evangelization is helping youth rediscover or discover for the first time the richness of the Gospel. However, once teens join a youth group and appear to begin to be engaged, what happens then? Pope Francis at World Youth Day said, “Sharing the experience of faith, bearing witness to the faith, proclaiming the Gospel: this is a command that the Lord entrusts to the whole Church, and that includes you…” Therefore, part of the whole Church’s mission is to make it known that teenagers are not only called to be disciples of Jesus, but to be apostles; to partake in the apostolic mission and responsibility of Jesus and the Church. Spending the summer ministering to older high school students from across America, from Louisiana to Michigan, has shown me one very effective way at helping youth to recognize their calling to be apostles, and to discover and then use their God given talents to participate in a certain liturgical ministry. Everything the Church does flows from one thing- the celebration of the Eucharist. Therefore, if we are trying to keep youth in the Church, or help them to realize their calling to be apostles, why would we not involve the youth in the most important work that the Church does? If youth understand the liturgy and participate in it, then they will be able to understand and participate in the Church, because the liturgy is the greatest teaching tool the Church has. “Renewing the Vision,” a landmark document on youth ministry by the USCCB says evangelization, “calls young people to be evangelizers of other young people, their families, and the community.” Once youth become involved in the liturgy and understand it, it becomes the natural next step for them to evangelize others and in my experiences and probably yours, it becomes much more likely that they will feel a part of the Church and stay in the Church. Conor Boland is a College Ministerial Intern for One Bread One Cup, at Saint Meinrad Seminary & School of Theology and is an undergraduate at the Catholic University of America.  When you hear the word ‘hospitality’, what comes to mind? Like most people, I bet you think of hotels, or in some cases, you may think of that one aunt you have who always makes sure everyone’s glass is full and everyone has a seat. If you’re in ministry, ‘hospitality’ may now be synonymous with having coffee and light pastries at early morning meetings. But in a Benedictine sense, hospitality is very different. July 11th marks the Church’s feast of St. Benedict. In the early sixth century, St. Benedict wrote a Rule that he wanted his monks to follow. In 73 short chapters, St. Benedict tried to lay out an entire monastic way of life, so he certainly had a lot of ground to cover. He wrote about everything; from how an abbot should be chosen to how much monks were to eat and drink and where they were to sleep. He also devoted an entire chapter to how guests were to be received and treated. This whole chapter, which is quite brief, can be summed up in the first phrase the Founder writes, “Let all guests who arrive be treated as Christ…” (Ch. 53). Benedict goes into specifics on how guests are to be welcomed and fed, but it all goes back to Christ Himself saying “I came as a guest, and you received Me” (Mt. 25:35). St. Benedict understands, and wants his monks to understand, that Christ can be found in everyone. The first phrase of the last paragraph is a perfect summary of the Gospel message as well, “In the reception of the poor and of pilgrims, the greatest care and solicitude should be shown, because it is in them that Christ is received…” (Ch. 53). How do we treat the stranger on the street, the man selling us a magazine, the immigrant, or the receptionist? Remember also, this does not apply to just the stranger. How do we treat those that we see every day: the coworker, roommate, friend, or classmate? Are these people just a means to an end, are they here for our convenience or happiness, or are they Christ to us? Are we treating them as Christ incarnate or just as another person we have to deal with? Most likely we do not fall into either extreme, but every time we fall short of treating a person as Christ, we fall short of treating God as God. To be hospitable, we do not need to follow the exact instructions of St. Benedict. Our hospitality, like his, should be rooted in charity, in love. It can be quite simple: a smile, a since greeting, or the most common one at my alma mater, the holding of a door for a distant stranger. Hospitality is the easiest way to build up the Kingdom of God here and now. When we welcome the guest, greet the stranger, or feed the hungry, we are doing these things for both God and neighbor. By being hospitable, we are fulfilling the greatest commandment. Let us pray for the intercession of St. Benedict today, asking him to pray for us, that we may be hospitable, welcoming, and loving in every interaction we have. Michael Phelan is in his second and final year in the Echo Program at the University of Notre Dame. He is a graduate of Saint Anselm College, a Benedictine school, in Manchester, N.H.

The first time I stayed in a Benedictine monastery, I was struck by the silence, especially since the monastery was only a few hundred feet away from my dorm (which was never silent). During meals in the refectory, walks in the hallways or the monastic cloister, down time in my assigned cell, both at daytime and during the night, there was a serious, purposeful silence. In his Rule, Saint Benedict constantly encourages his monks not to speak too much, and especially to abstain from vulgar and scurrilous speech. But what is the point of this silence? Why does Saint Benedict praise it so highly? “Listen carefully.” This is the first and most basic instruction laid down by Saint Benedict in his Rule, written for monks in the early sixth century. He was telling his monks to perk up and pay attention, because important guidelines for monastic life were coming their way in the ensuing 73 chapters. His advice, in those two words, seems to sum up much of Benedictine spirituality. Saint Benedict’s world was not too different from the world we live in today. His life began in the year 480, only four years after the fall of the Roman Empire. He was a witness of political upheaval, international war, and class warfare. This is not much different from our times. His answer to all these problems, however, was not to escape from the world in a monastery, but to find a place in which he could seek God in a stable environment. Why, then, is St. Benedict’s first piece of advice to listen? Saint Benedict was a keen observer of the human person, and he recognized what was separating people: noise, both internal and external. Even today, how comfortable are we with silence? Think about it. We need music in order to drive down the street; we need music to go for a run; some even need ‘white noise’ in order to fall asleep. How often do we see people, old and young, with their nose buried in a phone or searching for the next song instead of enjoying and appreciating God’s gift of creation around them? Or internally, are we truly listening to the other person in the conversation, instead of just thinking about what we will say next? Silence is the first step. Once we stop talking, turn off our music or put down our phones, then we have to quiet ourselves on the inside. We need to begin, in silence, to find Christ in the other. In each one of us there is an innate yearning, which can only be discerned and realized when we slow down from our own business and busyness and understand that we all want something more. God speaks in the silence of our hearts. Therefore, you have to “attend with the ear of your heart” to what God is calling you to. The Prologue of the Rule of Saint Benedict has, in my opinion, some of the most beautiful language ever written. I would suggest to anyone who has never read it to get it immediately. Saint Benedict wrote an amazing line – a rhetorical question – “What, dear brothers, is more delightful than this voice of the Lord calling to us?” But how can we ever hope to hear this delightful voice of the Lord unless we stop and listen? Saints Benedict and Scholastica, pray for us! Michael Phelan is in his final year in the Echo Program at the University of Notre Dame and serves as an Apprentice Catechetical Leader at Nativity Catholic Church in Brandon, FL, in the Diocese of St. Petersburg. He is a graduate of Saint Anselm College, a Benedictine college, in Manchester, NH.

|

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

About |

Media |

© COPYRIGHT 2024 | ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

RSS Feed

RSS Feed