|

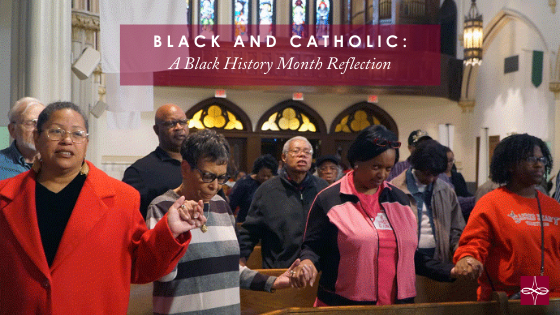

As a Catholic of African descent, I am honored and privileged by this unique opportunity to discuss the beautifully diverse Catholic Church throughout the world, the significant contributions that those of every ethnic background have made in building up the Body of Christ, and how we can arrive at racial healing and reconciliation. The Catholic Church is made up of the faithful of every ethnic background, the young and old, both male and female, and several distinct cultural settings. In other words, we Catholics come from every realm of the human experience, and are united in our baptismal fidelity. As a black Catholic, my religious heritage spans all the way back to biblical times, including when Saint Philip the Apostle brought the Good News of Jesus Christ down into Ethiopia (see Acts:8:26-40). Both African and African-American saints, including those in this extensive list from Catholic Online, have enriched the Church for nearly two millennia. Likewise, the modern era features some black candidates for sainthood, including those appearing in the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ webpage titled “On the Path to Sainthood: Leaders of African Descent.” I encourage everyone of good will to read through the biographies of the figures listed in both of those sites, in order to gain a greater appreciation for the manifold ways that they have built up the Body of Christ, per the Apostle Paul’s Letter to the Romans: “For as in one body we have many parts, and all the parts do not have the same function, so we, though many, are one body in Christ, and individually parts of one another” (Romans 12:4-5). The calendar year 2020 brought numerous challenges to those of every faith, both in the United States and around the globe, as the world confronted the COVID-19 pandemic and matters of racial discord were brought to the fore in the United States. I think often of how far we have come as a nation in terms of fostering peace and harmony between people of every ethnic background here in the United States. For instance, my father, Charles McClain, Sr., who was born in Durham, North Carolina, in 1936, and lived under segregation well into his early adulthood, probably did not fathom during his youth that he would one day see three of his sons (my brother Eric, my brother Jaris, and me) go on to marry white women. We can attest that this is, in a way, a fulfillment of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, affirmation from his “I Have a Dream” speech of August 28, 1963, declaring that “I have a dream that that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character,” and that “one day… little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.” Yet, as with many quests for justice, this is easier said than done. However, since we profess our faith in Jesus Christ, we have inspiration from the Gospel, since Jesus commands (not suggests) to “love your neighbor as yourself” (Mark 12:31), and to “do to others as you would have them do to you” (Luke 6:31). To facilitate healing and reconciliation, we must have best intentions and give others the benefit of the doubt when they are striving to learn more about their brethren of other ethnic backgrounds and cultures. As such, every endeavor in this regard should be marked by true charity and prayer prior to the initiation of any sociopolitical engagement, all of which must be informed by the Gospel and its imperatives if we are to call ourselves disciples of Jesus Christ. For this reason, I urge the faithful to read books on racial reconciliation and healing from a Christ-centered perspective. A couple of books that come to mind are Joseph Pearce’s Race with the Devil: My Journey from Racial Hatred to Rational Love (TAN Books, 2013) and the late Fr. Ubald Rugirangoga’s Forgiveness Makes You Free: A Dramatic Story of Healing and Reconciliation from the Heart of Rwanda (Ave Maria Press, 2019). Of note, Fr. Ubald passed away from complications related to COVID-19 on January 7. You can read more about his life and ministry in this tribute provided by Ave Maria Press. I love teaching my children and students about being an African-American Catholic, just as I enjoy learning about my wife’s Irish-American Catholic heritage and many other avenues of cultural diversity within the Church. Let us draw each other to embrace the sacramental life and the Church’s timeless moral standards in order to reinforce the Body of Christ. May God bless you.

0 Comments

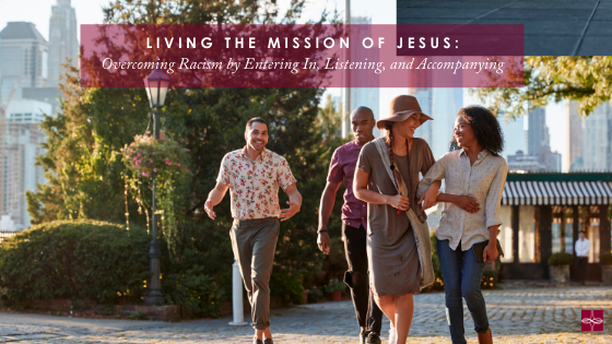

11/19/2020 Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship - Top Quotes from Pope Francis' Latest EncyclicalRead NowOn the vigil of the Feast of St. Francis of Assisi, the saint who influenced the choosing of Pope Francis’s papal name, Pope Francis released the encyclical Fratelli Tutti on fraternity and social friendship. Beginning with the example of St. Francis himself and continuing with the parable of the Good Samaritan, Pope Francis calls the world once again to consider the common good and to strive for unity based on fraternal charity. In doing so, he reminds humanity of an important truth: that we belong to one another. In this blog series, I’ll be sharing some of my favorite quotes from the pope’s latest encyclical. May they bring you peace, hope, and joy as we continue to grow and adapt in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on our world. “Let us dream, then, as a single human family, as fellow travelers sharing the same flesh, as children of the same earth which is our common home, each of us bringing the richness of his or her beliefs and convictions, each of us with his or her own voice, brothers and sisters all” (FT, 8) Today I believe that many of us have forgotten to dream. We are mired down with anxiety, isolation, pandemic fatigue, stress, financial and political uncertainty, or disillusionment. In Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis reminds us to dream and to hope. There is room for each person at God’s table. Each person brings their own gifts, talents, knowledge, expertise, experiences, and self to the world. Rather than reject our differences, it is important to acknowledge and even celebrate the richness in our human diversity. We are many parts, but one body. Let us celebrate our humanity and practice dreaming once again—of unity, of peace, of justice, of truth, of love. “Instances of racism continue to shame us, for they show that our supposed social progress is not as real or definitive as we think” (FT, 20). As several incidents within the United States have reminded our nation once more, racism is a sin which directly contradicts the truth that all people are born with equal dignity in the image and likeness of God. The sin of racism continues to be present in our world, and eliminating it involves the intentional work and learning of each person. This process includes listening to other’s stories and journeys, learning about and from history, conducting a personal examination of conscience, and intentional action to change systems and structures of racism. Pope Francis reminds us that racism is intolerable, not only among Catholics, but among mankind as a whole. “True, a worldwide tragedy like the Covid-19 pandemic momentarily revived the sense that we are a global community, all in the same boat, where one person’s problems are the problems of all. Once more we realized that no one is saved alone; we can only be saved together” (FT, 32) Although the COVID-19 pandemic has wrought havoc on the way we live, times of hardship also remind us of what’s important. Often, we re-focus on our priorities because we are reminded not to take them for granted. Many turn to faith, family, and community and are more likely to help those who are less fortunate. Practicing gratitude is an essential component of not only surviving but thriving in times of hardship. Pope Francis points out that tragedies such as COVID-19 can bring humanity together in a common bond of fraternity. Let us turn outward during this time and use our talents and resources to bring joy, love, and hope to others. “We have the space we need for co-responsibility in creating and putting into place new processes and changes. Let us take an active part in renewing and supporting our troubled societies. Today we have a great opportunity to express our innate sense of fraternity, to be Good Samaritans who bear the pain of other people’s troubles rather than fomenting greater hatred and resentment” (FT, 77) Co-responsibility is an important theme at the Catholic Apostolate Center that has been given even greater attention in the Church today. It involves collaboration from the beginning and values the important contributions each person brings to the Church and world. St. Vincent Pallotti, patron of the Catholic Apostolate Center, understood that the Church cannot thrive and spread the Gospel without the active participation of the clergy, religious, and laity. Today, Pope Francis reminds us that we all have a role to play in the renewal of the Church and world. This begins when we can accompany our brothers and sisters, stand in solidarity with those who are hurting, and bring them the joy of the Gospel. “Solidarity finds concrete expression in service, which can take a variety of forms in an effort to care for others” (FT, 115) Charity comes alive in works, just as St. Paul says, “faith without works is dead.” The Gospel is lived today through our actions—an understanding promoted in Catholic Social Teaching and exemplified through the corporal and spiritual works of mercy. It is one thing to express solidarity with our brothers and sisters, but a very different thing to walk alongside and serve them. Pope Francis is calling us to both. As we are reminded in Gaudium et Spes, “Man…cannot fully find himself except through a sincere gift of himself” (24). “Nor can we fail to mention that seeking and pursuing the good of others and of the entire human family also implies helping individuals and societies to mature in the moral values that foster integral human development...Even more, it suggests a striving for excellence and what is best for others, their growth in maturity and health, the cultivation of values and not simply material wellbeing. A similar expression exists in Latin: benevolentia. This is an attitude that ‘wills the good’ of others; it bespeaks a yearning for goodness, an inclination towards all that is fine and excellent, a desire to fill the lives of others with what is beautiful, sublime and edifying” (FT, 112) In the Christian worldview, politics, economics, culture and society must be built and exist for the common good. They are man-made structures designed to serve this purpose. In pursuing the common good, we aim to create a society in which mankind can flourish as a result of respect for every person’s inherent dignity. As St. Thomas Aquinas stated, “Love wills the good of the other.” Pope Francis echoes this truth and reminds us that willing this good is comprehensive: we must care about one another’s spiritual well-being as well as our physical well-being. When man’s fundamental needs are met—when he is cherished, nurtured, respected, fed, and rested—he is better able to “fill the lives of others with what is beautiful, sublime and edifying.” He is able to reach out and better experience and rest in the divine. To learn more about Fratelli Tutti, please click here. 6/30/2020 Living the Mission of Jesus: Overcoming Racism by Entering In, Listening, and AccompanyingRead NowThe din of breakfast time in a house full of little ones required that I practically yell to my husband to be heard over requests for more milk: “I just feel so sad for our country. I feel sad that so many people are suffering. I’m sad about how devastated God must feel.” Before he could respond, my sweet, sensitive 5-year-old hugged my legs. “It’s okay to feel sad, Mom. But, why are you sad for our country?” And so our dialogue began. I gently told him about the injustices being faced by our Black brothers and sisters. I reminded him that God made each of us in His image, and that we are each deeply loved by Jesus. I reminded him that racism is a sin, and that Jesus conquered our sins by His death on the Cross. We love Jesus and honor His sacrifice by turning away from sin. And then I told him that we have work to do: as Catholics, we get to be like Jesus by fighting against racism. As believers, we are called to make the world more loving and just. So together, we enter this mission of Christ. Our baptism calls us and sends us out, equipping us to live as members of the Body of Christ. The Catechism calls us “members of each other, (CCC no. 1267)” and as such, we have a responsibility to live that way. Using the life and love of Jesus as the guiding principal of our faith, we are invited to acknowledge the suffering of those around us. Saint Paul writes in his letter to the Corinthians, “If one part suffers, every part suffers with it; if one part is honored, every part rejoices with it. Now this is the body of Christ” (1 Corinthians 12:26). This is unity as the Body of Christ: a people not positioned as ‘left’ or ‘right,’ for only the unborn or for only Black lives, but positioned at the foot of the Cross. Our Church, informed by the Gospels, calls us together to this work to uphold the dignity of the person, letting Jesus show us the way. Jesus was moved with compassion. At the death of Lazarus, he wept. At the woman’s desperation for healing, he allowed himself to be touched by her. He entered into the woman at the well’s loneliness and shame and met her with mercy. Jesus showed up heart first, revealing how we might accompany each other. As a white woman, I cannot know the suffering of the Black community. I can, however, emulate Jesus by allowing myself to hear and see hurt and be moved deeply by it. Instead of rationalizing, self-aggrandizing, or refusing to acknowledge the pain of another’s story, I open my eyes to see the brokenhearted—even when it challenges me, even when it hurts. Like Jesus, I weep for the loss of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Rayshard Brooks, and so many others. I allow myself to feel and enter into the pain. I lean in until it makes me want to do something. Jesus stood with the vulnerable. God made flesh dwelled among us and was moved with compassion for his people. Seeing the suffering of Martha and Mary, he raised Lazarus from the dead. At the ailing and fear of the bleeding woman, he extended healing and peace. He saw the shame of the woman at the well and revealed himself as God to her, declaring her worthy of His life-giving water. In these examples and countless others, Jesus reveals himself as unapologetically for and with the least of these. As Catholics, we are called to this mission. In response to the just anger of our Black brothers and sisters, we stand in solidarity with all who experience the sin and effects of racism . Moved by this pain, we cry out to our Father for healing and peace. Using our voices, votes, and dollars, we stand for and with the Black communities and all affected by the sin of racism, declaring the value of each life and the dignity of each person. I am tempted to avoid this work. Showing up heart first the way Jesus did requires a vulnerability and humility I often lack. I become disproportionately concerned about being comfortable and being right. I am tempted to keep my head down, refusing to be moved and challenged by new voices and stories. Yet, I am called to look up. When I pridefully insulate myself from the pain of a hurting person or community by my refusal to enter in, openhearted, I deny the dignity of their personhood by not validating their experience. By guarding my hardened heart, I fail my baptismal calling. Jesus concerned himself more with loving the low in spirit than the repercussions of caring. He entered in, listened, and loved each person—especially the marginalized. So today I seek to live like Jesus. I choose to sit in sorrow for the pain of my Black brothers and sisters. I lift up my voice in prayer, confident that God sees and cares deeply about justice, unity, and life. I choose to look to the mission of Jesus to remember my own. Join me.

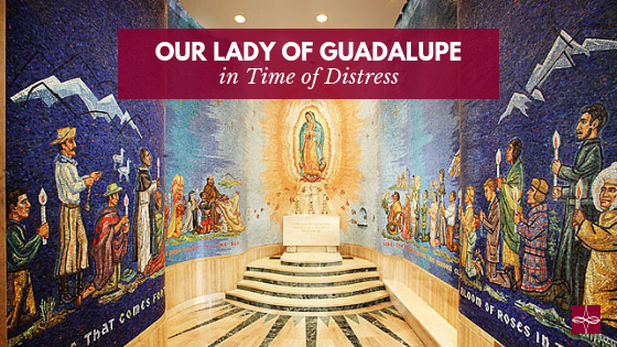

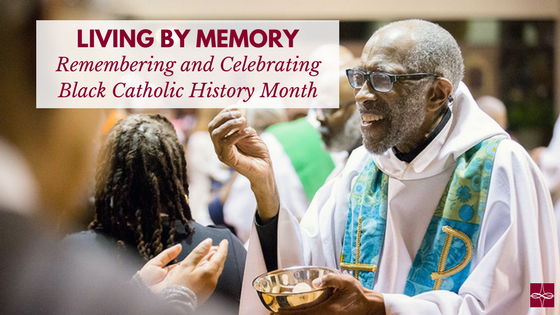

As a nation, we celebrate Martin Luther King, Jr. Day on January 21st. Does this mean anything special for the Church—for Catholics, even? Catholics have much to learn and celebrate about the Baptist pastor, preacher, and prophet. The more we consider how far we have come as a nation and as a human race since Dr. King met his tragic end on April 4, 1968, the more we sense, I think, just how far we have to go to realize his Dream. When I think of Dr. King, I think of justice. Biblical justice. To recall a famous quote (King’s paraphrase from Theodore Parker), “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” As our nation honors Dr. King in a few days, I think it might be wise to contemplate for a moment the role of justice in our discipleship, which is an integral aspect of our baptismal identity as priest, prophet, and king. As a pastor and preacher, Martin Luther King, Jr. understood deep in his bones the kerygmatic nature (from “kerygma”) of true justice. Justice is a gift of Jesus. Like all gifts and graces from God, it is meant to be multiplied and shared. Even in the most difficult times of persecution, Dr. King proclaimed the gift of justice. In his famous “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” Dr. King wrote the words, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Dr. King (who earned a Ph.D. in Philosophy from Boston University) quotes St. Thomas Aquinas in defining an unjust law as “a human law that is not rooted in eternal and natural law,” and then adds a simple explanation: “Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust.” St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1774), the great theologian of the Middle Ages and among the greatest in the history of the Church, defined justice as giving the other what is their due. Thomas Aquinas even defines “religion,” which is a virtue, as a form of justice, because it gives God the worship and adoration that is owed to him. First, can we ask ourselves where justice is still lacking in our world and in our own Church insofar as it is, alongside its spiritual identity, an institution composed of fallible, sinful human beings? Any lack of justice is a sure sign that we, the Church, have become adept in talking about the Gospel but have yet to take living it just as seriously. In her ongoing task of renewal, the Church must recover a robustly biblical, prophetic vision and conviction that justice is not accessory to the Gospel. Fortunately, in my own observations and ministry, I have seen that many young Christians are mending the gap that seems to have developed between “social justice Christians” and “liturgy and doctrine Christians.” This distinction is foreign to Aquinas and King, and the extent to which we buy into this split is the sign that we have allowed our faith to be compromised by the politics of the day. To offer one way of restoring this divide, in his letter Dr. King writes, “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” What if we thought about our baptismal garment, symbolic of putting on the life of Christ, as also the Church’s “garment of destiny”? Salvation and justice are the garment that clothes the body of Christ, the Church. One way of looking at Dr. King’s quote about the moral arc is to see it as a challenge that is not “way out there” in the universe, but as an invitation to bend and mend our personal lives toward justice. What might it imply to bend our lives? A change of habit or lifestyle, resisting our initial unkind or selfish response or natural inclination, and going out of our way to change the trajectory of our relationship with other people, our nation, and even creation. This is the message of “integral ecology” Pope Francis teaches in his encyclical letter Laudato Si. Dr. King saw God’s providential hand at work on a cosmic level, and as Catholics, we recognize the need as disciples to participate in God’s grace, and that includes justice. Authentic justice takes work, effort, struggle, and at times—as many true prophets in Scripture and history have experienced—persecution. Not all of us are called to create justice in the same way, yet we are all called to create justice in some way. Question for Reflection: What is one concrete step you can take to help create a more just situation in your family, school, workplace, or other sphere of influence today? To learn more about Catholic Social Teaching, please click here. It might be frightening to look at our culture today. There is the sense that a Catholic worldview is not welcome. Some feel confusion about what it means to be Catholic. A culture of death and darkness seems to oppose God’s love. One wonders how the Holy Spirit will work in the world and through the Church amidst such hostility and division. This is not the first time the Church has encountered such a moment. The 1500s were also a tumultuous era. At the beginning of the century, in, 1517, the Protestant Reformation started. Then the English Reformation of Henry VIII began in 1534. The Church responded with the Counter-Reformation. A new order, the Jesuits, was founded in 1540 and in 1545, the Council of Trent was initiated. By that time, millions of people had left the Catholic Church. It seemed to be a time of waywardness and chaos. How was the Holy Spirit going to work in such a world? Simple: By sending the Mother of God not to the Old World—Europe—but to the New World. Specifically, Mary appeared at the Hill of Tepeyac in 1531 to ask a 57-year-old peasant named Juan Diego to speak to Bishop Zumarraga about building a chapel in her honor there. This is where Our Lady, on December 9th, made her first apparition to her “Juanito” or “dear little Juan.” She told him that she was “the perfect and ever Virgin Holy Mary, Mother of the God of truth through Whom everything lives, the Lord of all things near us, the Lord of heaven and earth.” On her last visit on December 12th, Mary arranged roses in Juan Diego’s tilma and sent him to the bishop to ask him again to build a shrine to her on that spot. When he opened his tilma to show the bishop the roses, it revealed her image, which can still be seen in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City. Mary appeared on a hill that was already sacred to the ancient peoples of Mexico as a shrine to a mother goddess. She was dressed as an Aztec princess, pregnant with the God who made us. She spoke to a humble native of the land and called him her “youngest and dearest son.” Before her apparition, approximately 200,000 Native Americans had been baptized. Between the time of her visit to Juan Diego and her message to Bishop Zumarraga and their deaths in the spring of 1548, over 9 million ancestral peoples had received the gift of faith and baptism. In a time of great conflict, colonialization, and racial tension, Mary appeared on this continent to tell Juan Diego, “I am truly your merciful Mother, yours and all the people who live united in this land and of all the other people of different ancestries, my lovers, who love me, those who seek me, those who trust in me.” She is the mother of all the peoples in the land, then and now. She reminds us that what truly defines us is not our status or ancestry, but our membership in the Body of Christ. It can be a struggle to know and act like a member of Christ’s Body when there are so many opposing forces. What does it mean to act like a Christian, vote like a Christian, shop like a Christian, or even speak like a Christian? It means that we take our fears, our sorrows, our hopes, our hurts, and our weeping not to a political party or an outlet mall; but to our Mother, who in turn presents them to her Son. Am I not here, I, who am your Mother? Are you not under my shadow and protection? Am I not the source of your joy? Are you not in the hollow of my mantle, in the crossing of my arms? Do you need anything more? -Our Lady to Juan Diego Question for Reflection: In times of distress, do you turn to Our Lady to bring you closer to Christ? Just down the street from where I study and serve in my home Archdiocese of Baltimore is our nation’s first Catholic cathedral, the Basilica of the Assumption, a visible testimony to the faith of the first Catholics in the newly formed United States of America. Yet every time I visit that holy place, I’m reminded by the physical space that for many years worship was segregated and black Catholics were required to sit in the balcony. Our family of faith in Baltimore included heroic individuals and communities like that of Mother Mary Lange (1794-1882), founder of the first African-American religious order, the Oblate Sisters of Providence, and the ministry of the Josephites. Their creative witness and ongoing presence in our communities today serve as a constant reminder that their mission lives on and has work yet to do. Since 1990, the Church in the United States, through the work of the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus (NBCCC), has designated November as Black Catholic History Month. In a special way, the testimony of black Catholics reminds us all that as disciples of Christ, we live by memory. Celebrating this month reminds the Church just what it is that we are responsible for remembering. The act of remembering is a moral and spiritual task, part of the Church’s call to combat the sin of racism and seek new forms of reconciliation with sins of the past. Additionally, I’d like to suggest that memory lies at the heart of the Church’s celebration of word and sacrament, and briefly reflect here on why remembering our Church’s black history is so important for faithfully celebrating God’s word and sacrament each and every day. Those who attend or have attended a parish with a strong black Catholic presence will often recognize the power of the proclamation and preaching of God’s word. In particular, this tradition of preaching reminds Catholics that our Church preaches and teaches a truly liberatory word. Jesus Christ came to deliver God’s people from all forms of bondage and oppression, restoring us to freedom. Our biblical faith makes clear that participation in the Exodus event is intrinsically connected with our participation in the Passover. As Catholics, this means we are fed by God’s word and sacrament, particularly the Eucharist. At the Institution of the Eucharist at his Last Supper, Jesus instructed his Apostles to “Do this in memory of me” (Lk 22:19). The sacrifice of the Mass is an act of remembrance, called anamnesis, that re-presents Christ, making Jesus truly present here and now in the species of bread and wine. (I invite you to read Father Raniero Cantalamessa’s reflection.) That act of remembering is the basis for our act of thanksgiving (literally, “eucharist”). But it is impossible for us to give thanks for what we cannot remember. Does Christ’s presence at the altar then lead us onward to become more aware of Christ’s presence in our brothers and sisters who remain subject to forms of injustice and oppression elsewhere? To this end, our bishops offer resources on how to respond to sins of racism, an important way to publicly live out the interior transformation we receive in the Eucharist. While we live by memory, we do not simply live in the past; we are called to faithfully live out of our past. We live by memory as a sign of our hope that since God gave us a past, he promises us a future. Black Catholic History Month serves as a reminder that we have a history worth remembering and celebrating, so that we may go on living in the freedom to which Christ daily calls us. For more resources, we invite you to visit our Cultural Diversity Resources page and scroll down to the section on African American/Black Catholics. Click here to read Open Wide Our Hearts: The Enduring Call to Love, a pastoral letter from the USCCB against racism Questions for Reflection: How does remembering the past help us to live more faithfully and hopefully in the future? How have you seen our Church benefit from the diversity of its members? *This post was originally published on the Ad Infinitum Blog on November 2, 2017 For more information about Black Catholics in the US, check out the resources created by the National Black Catholic Congress in collaboration with the Catholic Apostolate Center: Just down the street from where I study and serve in my home Archdiocese of Baltimore is our nation’s first Catholic cathedral, the Basilica of the Assumption, a visible testimony to the faith of the first Catholics in the newly formed United States of America. Yet every time I visit that holy place, I’m reminded by the physical space that for many years worship was segregated and black Catholics were required to sit in the balcony. Our family of faith in Baltimore included heroic individuals and communities like that of Mother Mary Lange (1794-1882), founder of the first African-American religious order, the Oblate Sisters of Providence, and the ministry of the Josephites. Their creative witness and ongoing presence in our communities today serve as a constant reminder that their mission lives on and has work yet to do. Since 1990, the Church in the United States, through the work of the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus (NBCCC), has designated November as Black Catholic History Month. In a special way, the testimony of black Catholics reminds us all that as disciples of Christ, we live by memory. Celebrating this month reminds the Church just what it is that we are responsible for remembering. The act of remembering is a moral and spiritual task, part of the Church’s call to combat the sin of racism and seek new forms of reconciliation with sins of the past. Additionally, I’d like to suggest that memory lies at the heart of the Church’s celebration of word and sacrament, and briefly reflect here on why remembering our Church’s black history is so important for faithfully celebrating God’s word and sacrament each and every day. Those who attend or have attended a parish with a strong black Catholic presence will often recognize the power of the proclamation and preaching of God’s word. In particular, this tradition of preaching reminds Catholics that our Church preaches and teaches a truly liberatory word. Jesus Christ came to deliver God’s people from all forms of bondage and oppression, restoring us to freedom. Our biblical faith makes clear that participation in the Exodus event is intrinsically connected with our participation in the Passover. As Catholics, this means we are fed by God’s word and sacrament, particularly the Eucharist. At the Institution of the Eucharist at his Last Supper, Jesus instructed his Apostles to “Do this in memory of me” (Lk 22:19). The sacrifice of the Mass is an act of remembrance, called anamnesis, that re-presents Christ, making Jesus truly present here and now in the species of bread and wine. (I invite you to read Father Raniero Cantalamessa’s reflection.) That act of remembering is the basis for our act of thanksgiving (literally, “eucharist”). But it is impossible for us to give thanks for what we cannot remember. Does Christ’s presence at the altar then lead us onward to become more aware of Christ’s presence in our brothers and sisters who remain subject to forms of injustice and oppression elsewhere? To this end, our bishops offer resources on how to respond to sins of racism, an important way to publicly live out the interior transformation we receive in the Eucharist. While we live by memory, we do not simply live in the past; we are called to faithfully live out of our past. We live by memory as a sign of our hope that since God gave us a past, he promises us a future. Black Catholic History Month serves as a reminder that we have a history worth remembering and celebrating, so that we may go on living in the freedom to which Christ daily calls us. For more resources, we invite you to visit our Cultural Diversity Resources page and scroll down to the section on African American/Black Catholics. We invite you to read Cardinal Wuerl's Pastoral Letter, The Challenge of Racism Today, by clicking here. Questions for Reflection: How does remembering the past help us to live more faithfully and hopefully in the future? How have you seen our Church benefit from the diversity of its members? "With all vigilance guard your heart, for in it are the sources of life."

-Proverbs 4:23 When I was first hired to teach at my high school and was told I was going to be teaching social justice, I was very excited. I had learned a lot from different teachers over the years about social justice issues plaguing our society and I wanted to ignite a fire in my students that they could make a difference and impact society. I knew it was going to be a challenging topic to teach, especially to high school students, but I never realized the toll it would have on me. Halfway through my first year of teaching, one of my students handed me a post it note with Proverbs 4:23 written on it. The interpretation she had written was “Above all else, guard your heart. For everything you do flows from it.” It took me some time to realize what she was trying to tell me through this passage, but once I realized what she meant it changed my thinking and my outlook on what I was teaching and the world around me. Some of the topics we cover are racism, prejudice, and poverty. I very quickly realized that in order to make the girls aware of the problems in the world around them, I had to bring in real world examples. At the beginning of every class, my students were invited to bring in news articles or experiences of their own that related back to the topic. I would also research different events or issues myself. After reading and hearing somewhere around 100 different examples of where our society has gone wrong and how we are hurting each other, I began to get a sense of hopelessness. My heart began to hurt because we have so many solutions on how to make our society better, and still nothing ever gets done. It reached a point that I didn’t think society would ever change and I started to stop believing in what I was teaching. Every morning we wake up and turn on the news and see news report after news report of our society tearing each other apart and forgetting the value that each one of us has. That kind of destruction and hurt takes a toll on you; especially your heart, and can make you feel helpless. My student recognized what was happening to my heart and saw me breaking after every news report and life experience I heard in class. She left me this note to remind me that despite the world we are living in, we have to guard our hearts because that is where your drive and spirit comes from. She showed me that if I protect my heart and keep faith and hope in God and the world he created, things could get better. It is really easy to lose faith and hope and have your heart get hurt if you don’t guard it. Once you lose hope and your heartbreaks, everything in your life is affected. Your heart is the center of everything and it drives your life and your passion. If you don’t guard it and keep it safe, you can’t be the best version of yourself. Erin Flynn serves as a high school religion teacher in the Diocese of Brooklyn, New York. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

About |

Media |

© COPYRIGHT 2024 | ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

RSS Feed

RSS Feed